As China continues to assert itself as a global power—both financially and militarily—the South China Sea appears to be where the country wants to make this geostrategic statement. Driving this new rush to have it all is a steadily increase of diplomatic and military maneuverings by the United States to contain China’s growing clout. As Asia Times correspondent, Billy Tea, will tell you in the detailed article that follows, it is not the first time disputes over the ownership of the South China Sea arise.

As China continues to assert itself as a global power—both financially and militarily—the South China Sea appears to be where the country wants to make this geostrategic statement. Driving this new rush to have it all is a steadily increase of diplomatic and military maneuverings by the United States to contain China’s growing clout. As Asia Times correspondent, Billy Tea, will tell you in the detailed article that follows, it is not the first time disputes over the ownership of the South China Sea arise.

Due to its presumably vast natural resources—petroleum and others—China and “some of its Southeast Asian neighbors, chief among them Vietnam, have long contested and sometimes clashed over different areas of the South China Sea. However, it was not until then United States Secretary of State Hillary Clinton declared at a July 2010 meeting of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) Regional Forum in Hanoi that the US had a “national interest” in the South China Sea that the situation started to spiral downward.” China’s industrial revolution is in dire of natural resources to keep its industries afloat. One can explain why just recently, China signed a 400 billion petroleum deal with Russia—a deal which will allow both countries to build a Siberian pipeline that will run to the Chinese heartland.

________________________________________________________________________

China’s grand plan for the South China Sea

By Billy Tea

Whether China’s decision to remove an oil exploration rig from waters hotly contested with neighboring Vietnam was motivated by bad weather, a completed mission, or rising diplomatic pressure from the United States, the move was the latest phase of Beijing’s grand plan to assert its sovereignty over the South China Sea.

While US Secretary of State John Kerry is scheduled to call for a “voluntary freeze” on all actions that could escalate disputes in the maritime area at a Southeast Asian security meeting this weekend, Beijing has already rejected the idea, saying it will retain its right to build on structures in its claimed areas. China’s nine-dash map claims over 90% of the 3.5 million square kilometer South China Sea.

There is a geo-strategic rationale rooted in realist foreign policies for Beijing’s rising assertiveness in the maritime area. In order to understand the present and anticipate the future, it is essential to look beyond recent events as isolated incidents and instead look towards Beijing’s long-term ambition for the highly strategic, hydrocarbon-rich sea.

China and a handful of Southeast Asian nations have long contested and sometimes clashed over different areas of the South China Sea. However, it was not until then United States Secretary of State Hillary Clinton declared at a July 2010 meeting of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) Regional Forum in Hanoi that the US had a “national interest” in the South China Sea that the situation started to spiral downward.

Clinton’s pronouncement was viewed by Beijing as a provocation and [a]step towards internationalizing the situation. Beijing, which has declared the area a “core interest” of its sovereignty, desires to resolve the disputes bilaterally with individual claimants and has resisted multilateral-led, international law-based solutions to the disputes. Beijing’s out-of-hand rejection of Kerry’s “voluntary freeze” recommendation is indicative of China’s hardening position on the issue.

Ever since Clinton’s speech, the South China Sea has been locked in a series of escalating action-reaction spats over individual features between China and Southeast Asian nations, including the Philippines and Vietnam. China’s 2012 stand-off with the Philippines over the contested Scarborough Shoal marked the beginning of Beijing’s more provocative approach to the disputes.

This year’s clashes between Chinese and Vietnamese boats near China’s HYSY 981 exploration rig, positioned in May near the contested Paracel islands, threatened to escalate into a full-blown conflict. China’s move was likely partly a reaction to Vietnam’s recent tender of exploration contracts to foreign energy concerns. Last November India’s Oil and Natural Gas Corporation (ONGC) signed an agreement with state-run PetroVietnam to cooperate in the hydrocarbon sector.

By May 2014, Vietnam had offered India seven blocks for offshore exploration in the South China Sea without competitive bidding. When India stated its plans to abandon oil block 128 in 2012, Hanoi asked Delhi to remain until 2014, demonstrating Hanoi’s desire to maintain India’s counterbalancing presence in the region. Hanoi has also opened the way to stronger strategic ties with the US to counteract Beijing’s rising assertiveness.

To be sure, the South China Sea conflicts are being driven in part by the potential bounty of oil and natural gas in the area. HYSY 981 is part of China’s so-called 863 Program, an initiative launched in March 1986 to narrow the technological gap between China and the world’s most advanced economies. Government agencies including the Ministry of Science and Technology and the National Development and Reform Commission provided strong support for the rig’s development.

To be sure, the South China Sea conflicts are being driven in part by the potential bounty of oil and natural gas in the area. HYSY 981 is part of China’s so-called 863 Program, an initiative launched in March 1986 to narrow the technological gap between China and the world’s most advanced economies. Government agencies including the Ministry of Science and Technology and the National Development and Reform Commission provided strong support for the rig’s development.

The rig provides China with the independent ability to drill for oil and natural gas in disputed parts of the South China Sea of which foreign companies may be unwilling to operate due to the political risks. After HYSY 981‘s move in May 2014, China deployed four more oil rigs (Nanhai 2/4/5/9) in June in the South China Sea with similar exploration missions to be completed later this year. The moves have sparked further diplomatic and economic disputes between China and Vietnam.

So what is China’s grand plan for the South China Sea? Former Chinese leader Deng Xiaoping’s strategic foreign policies of “bu chu tou” and “tao guang yang hui” – literally translating to “don’t stick your head out” and “hide brightness, nourish obscurity” – are still relevant but at the same time shifting towards a more assertive posture.

China no longer fully “hides in obscurity” about its capabilities and is increasingly willing to flex its military strength and technological prowess. HYSY 981 is a prime example of China’s indigenous technological advancement, including the deployment of a much improved coast guard to protect the rig from harassment by Vietnamese vessels.

Now that China has demonstrated its willingness to confront rival claimants in the South China Sea, it is likely for now “not to stick its head out” while gauging Vietnam’s and the international community’s full reaction to the incident. Behind this latest iteration of “action-reaction” over contested waters, China continues apace on its long-term, multi-phased plan to eventually assert dominance over the maritime area. The plan consists of three clear components, namely:

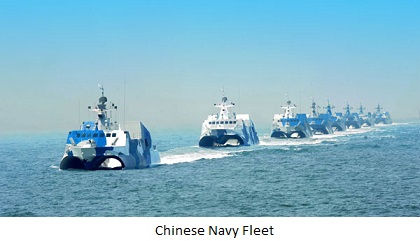

1) Boost military, particularly naval and air force, capabilities:

In March, China revealed its national 2014-2015 budget, with US$132 billion allocated to military expenditures, an increase of about 12% over the previous year. China’s military development has multiple purposes, and will not be solely aimed at asserting or defending its territorial claims in the South China Sea and East China Sea but will also be used as a deterrent for the situation in Taiwan and to displace US influence in the Western Pacific. According to Ronald O’Rourke, a US Specialist in Naval Affairs, China’s naval modernization efforts encompass:

anti-ship ballistic missiles (ASBMs)

anti-ship cruise missiles (ASCMs)

submarines

surface ships

aircraft, and supporting C4ISR (command, control, communications, computers, intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance) systems

maintenance and logistics, naval doctrine, personnel quality, education and training

2) Improve international Image:

2) Improve international Image:

China has been widely criticized for its lack of legal evidence to support its wide-reaching nine-dash map claims over the South China Sea. In the past, such international criticism would have had limited influence on Beijing’s policy, as demonstrated by its lack of response to the international outcry against its lethal suppression of the 1989 Tiananmen Square protests. However, China is now much more preoccupied with its global image. That was witnessed by Chinese authorities’ attempts to censor any negative representation of the country during the 2008 Olympic Games held in Beijing. In light of recent international criticism of its actions in the South China Sea, China has tried to bolster its claims through counter appeals to the United Nations. This new tactic, while not calling for a multilateral intervention in the disputes, is seen as a response to the Philippines filing of a case to the International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea (ITLOS) to assert its claim to disputed areas.

3.) Bolster legal claims:

In turn, China’s Foreign Ministry recently released a statement to the UN entitled, “The Operation of the HYSY 981 Drilling Rig: Vietnam’s Provocation and China’s Position,” which criticized Vietnam’s alleged provocations over the oil rig and provided a comprehensive outline of China’s claims to the Paracel Islands, including a Chinese government declaration issued on September 4, 1958. Moreover, it included photocopied pages from a geography textbook for Vietnamese ninth-graders published 40 years ago and a cover of a World Atlas.

Another method China is employing to support its claims is to bring sand to already established reefs and shoals in the South China Sea. The process, known as “island building”, is meant to support its claims within the definition of territory as set out in the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea. China apparently plans to move permanent populations on to the manufactured territories, thus strengthening its legal assertion to certain features and islands.

In order to foresee China’s potential actions post-HYSY 981, it is essential to understand its grand plan for asserting eventual dominance over the South China Sea. The question is not why did China remove the oil rig but rather what adaptive policies will it likely enact in the next phase. The escalating conflict, with or without US calls for calm, will not be resolved anytime soon. Yet the biggest mistake any onlooker could make would be to view the HYSY 981 event as a one-off occurrence rather than as a carefully calculated move that is part of a wider strategy.

Billy Tea is a Research Fellow at the Pacific Forum CSIS. His research interests include conflict prevention, conflict management and regional cooperation; Chinese foreign policy in Asia; and security and defense relations between Asia, Europe and the United States. He holds a BA in Political Science from UMASS Amherst and a MA in War Studies from King’s College London. www.atimes.com