CSMS Magazine

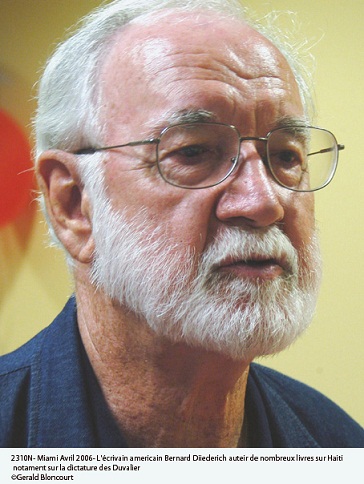

Bernard Diederich (left in the picture) is considered by many as an icon in Caribbean and Latin American literature. I met him for the first time during a tribute to Jacques Stephen Alexis back in 2006. Bernard is a good friend of Carrol Coates who translated JSA’s historical novel Compère Général Soleil. Carrol was also there, along with many important personalities from the world of Caribbean literature. Bernard was then 80, but listening to him and knowing his literary background, one could quickly sense that he was and still is a citizen of the world. But few people in the audience knew about his trajectories as a young man born in New Zealand from German-Irish parents who wanted to discover the world, but found himself stranded in Haiti on a December day of 1949. He fell in love with the place ever since. Most Haitians know of Bernard Diederich as the author of the world acclaimed book Papa Doc and The Tontons Macoutes. However, at the age of 86, Diederich shows no sign of slowing down. At the time we sat down for the chat, he had just released in French Le Prix du Sang (The price of Blood)—a lengthy manuscript, which according to him, represented the first of three volumes on the bloody period of the Duvalier dynasty. Last week, Dr. Ardain Isma spoke with him in a one-on-one interview at his suburban home in Southwest Miami, where he spoke about his dreams as a young man growing up in New Zealand, his wonder years in Haiti where he found his soul-mate and his aspirations for Haiti, his beloved and adopted country. It is with pleasure that we present this tireless writer to our CSMS Magazine readers.

A. I.: Good morning Mr. Diederich. It is a pleasure to have you at CSMS Magazine. To start it off, how long have you been writing, and what encouraged you to choose this path?

B.D.: I guess I have been writing all my life—scribbling first. During the Second World War, I had time to read a lot aboard ships in the Pacific, and during the post war period, I went to England to further my education. I had gone to war at age 16. My own country, New Zealand, a bucolic land of millions of sheep and only 3 million humans, had a socialist government and was an egalitarian society. But like a lot of young people after the war, I was not satisfied to sit still and live a happy, easy life like my brothers and sisters. We were a big family, two girls and four boys. Our ancestors arrived in New Zealand from Ireland and Germany in 1840 and 1870 respectively. (Details of growing up in New Zealand can be found in my book “The Ghosts of Makara.” See Amazon.

A. I.: New Zealand is a far off place when referring to Haiti, how did you end up in the Caribbean and in Haiti in particular?

B.D.: I ended up in Haiti by chance. Three wartime friends were fulfilling a dream that we might one day have our own vessel and sail the world. When the other two found a 95-foot sailing ketch in Nova Scotia, I took passage from England to Halifax and we fixed the vessel and sailed south. In Miami, we found a cargo for Haiti—windows for the El Rancho Hotel. It was December 1949. The second day in Port-au-Prince, thieves managed to sneak aboard and they stole my camera and film. My camera was everything. I had a deal with LIFE magazine to do a photo essay of what remained of the huge American bases in the Pacific built during the war with Japan. The story is contained in a two-volume book titled The Haiti Sun Years 1950-63 that I have yet to publish.

A. I.: Did you ever find your camera? What ever happened to your friends?

B. D.: I decided to quit our Pacific adventure and stay in Haiti to look for my camera. A half a century later, I still have not found my camera. I had to buy several of them later, as I became a photojournalist, believing in taking my own photos. My friends had problems sailing the Pacific, ran out of food and were saved from starvation by schools of tuna fish they harpooned.

A. I.: So, you stayed in Haiti. What did you do to survive?

B.D.: An American was at the time trying to start a daily English-Language paper in Port-au-Prince; and lawyer Jean-Claude Leger, whom I had met, introduced us. He called it Port-au-Prince Times. We were hired. Our job was to print the paper early in the morning at Le Matin. I was the donkey. I was responsible to put the paper out and sold advertisements. Dumarsais Estime was President at that time. In selling ads, I confessed to Mano Amboise and Roger Dorsinville, whom I had met, that Haiti needed a good newspaper with only Haitian news. The daily was filled with world news. That was how I launched in Sept. 1950 my own paper The Haiti Sun. It was a weekly publication. I had columns on ordinary Haitians and a Personality of the Week column. I made Daniel Fignole Personality of the Week before he was thrown into jail by Gen. Paul E. Magloire. Poet Emile Roumer brought me his Kreyòl columns, which I published. He came by boat from Jérémie, and he was an entertaining visitor to the Haiti Sun. One day, I may publish his Kreyòl columns. Mine was a Haitian weekly. I defended Haiti and, while I, at first, thought my endeavor would be a three or six-month experiment then return to Europe, it lasted way longer than that, until I got kicked out 13 years later. So Haiti became my nun.

B.D.: An American was at the time trying to start a daily English-Language paper in Port-au-Prince; and lawyer Jean-Claude Leger, whom I had met, introduced us. He called it Port-au-Prince Times. We were hired. Our job was to print the paper early in the morning at Le Matin. I was the donkey. I was responsible to put the paper out and sold advertisements. Dumarsais Estime was President at that time. In selling ads, I confessed to Mano Amboise and Roger Dorsinville, whom I had met, that Haiti needed a good newspaper with only Haitian news. The daily was filled with world news. That was how I launched in Sept. 1950 my own paper The Haiti Sun. It was a weekly publication. I had columns on ordinary Haitians and a Personality of the Week column. I made Daniel Fignole Personality of the Week before he was thrown into jail by Gen. Paul E. Magloire. Poet Emile Roumer brought me his Kreyòl columns, which I published. He came by boat from Jérémie, and he was an entertaining visitor to the Haiti Sun. One day, I may publish his Kreyòl columns. Mine was a Haitian weekly. I defended Haiti and, while I, at first, thought my endeavor would be a three or six-month experiment then return to Europe, it lasted way longer than that, until I got kicked out 13 years later. So Haiti became my nun.

A. I.: Was that really enough to get by in a land so new to you?

B.D.: At the same time I worked as a stringer first for International News Service, then Associated Press, then for The New York Times and then for Time and LIFE news Service. Stringing is a person who reports but is not a staff employee. The money I made from my stringing work came in handy in the 1957 period when merchants who believed I did not support their candidate boycotted my paper. So with the money I made abroad, I managed to subsidize my own newspaper.

A. I.: Was that all you needed to found your own newspaper?

B.D.: I was able to buy a linotype, Kelly press and a huge paper-cutting guillotine I purchased from La Phalange. My print shop was behind my editorial office. Some of my employees brought young Haitians, and they contributed much to my newspaper.

A. I.: Haiti can be a slippery place when it comes to politics. Have you ever encountered any difficulties with the government?

B.D.: In May of 1957 a decree in Le Moniteur contained my official expulsion from the country by the collegiate government. Senator Louis Dejoie who sought to be the “American” candidate found a story I had reported for Time Magazine unfavorable to his candidacy for President, and he controlled the interior ministry that issued my expulsion order. I packed my bag overnight and left the country only to return two weeks later when Daniel Fignole became interim president.

A. I.: Have you ever had any problem with the Papa Doc regime?

B.D.: I stayed in Haiti until 1963. On April 27th of that year, I was arrested at home by the Tonton Macoutes and delivered to the Penitentiary National. I stayed in jail for few days and then put on a plane into exile. I was one of the lucky ones. So many died that April of 1963.

A. I.: How did you come to write Papa Doc?

A. I.: How did you come to write Papa Doc?

B.D.: In 1965 a colleague from the Miami Herald kept asking me to write a book on Papa Doc. I refused. My concern was the safety of my in-laws in Haiti. Eventually when I realized that so many foreign news people knew little about Francois Duvalier, I became convinced it would be a service to the Haitian people who were suffering in silence. My friend, well known British writer Graham Greene, also encouraged me after he wrote The Comedians. My in-laws were tough and said, “go ahead.” We did and published Papa Doc in 1968. It was published in several languages. It was even pirated in Iran, and published in Farsi. It is still available at Barnes and Nobles.

A. I.: We know you also live in the Dominican Republic. How did end up there?

B.D.: Haiti was my love and I refused a job with Time in Brazil. So I moved with my Haitian wife and Haiti born son to Santo Domingo, and I reported from there. After covering the 1965 Dominican Civil War, in 1979 I published Death of the Goat published by Little Brown, Boston. Later it was published in Spanish and French as Death of the Dictator. In 2002, my photos of the Dominican Civil War were published in Santo Domingo as “Una camara testigo de la historia.”

A. I.: Did your stay in the D.R. last a long time?

B. D.: Time & Life News Service moved us to Mexico City in 1966, where I was Bureau chief for Mexico, Central America, Colombia, Venezuela and the Caribbean until 1981 when we reopened the Caribbean bureau in Miami. (See my book on Somoza: And the Legacy of U.S. Involvement in Central America, published by E. P Dutton, New York 1980)

A. I.: After retiring from the news service, what has become your new task?

B.D.: After retiring from Time Magazine a decade ago, I’ve devoted all my efforts to writing about Haiti. I had written Papa Doc from exile. So I’ve decided to go over the same period after the death of the Duvalier dynasty. I’ve devoted a decade to investigating the years of Papa Doc. My investigation will produce more than one book. The first is Le Prix du Sang, which was translated by an old friend from the early 1960s, Jean-Claude Bajeux. The second tome is the Jean-Claude Duvalier years—1971-86. The third is Titid. [The last two books have not been released.]

A. I. : In this new release, an entire chapter is devoted to Jacques Stephen Alexis. What prompted you to focus on Alexis while many contemporary historians from Haiti tend to shun the existence of Alexis’ works ?

B.D.: One story I reported in Papa Doc, which bothered me and took years in post-Duvalier years to learn the truth was “What happened to writer Jacques-Stephen Alexis?” I am now satisfied with what I’ve learned and published in Le Prix du Sang. I felt I owed it to him and his family and supporters. Because Jacques was a Marxist and [considered] “the enemy” his books were too hot to handle. Books and articles were banned. Writers during the Duvalier period had to struggle in the confines of a truly restrictive dictatorship. Jacques fell into the black hole. He has risen again.

A. I.: Why are you so dedicated to making the world know about the plight of the Haitian people?

B.D: Why? Because I owe it to Haiti. I have spent my life defending Haiti and I’ll continue until the end. Haiti has been a victim of foreign writers, who have written and said what they pleased to sell books. If I can help Haitians to know the truth, I think it is my biggest reward. Mine is a non-profit effort.

A. I.: After so many publications, do you become convinced that writing is a lucrative path that can get an author rich as most people tend to think?

B.D.: Getting rich? No. When I published Papa Doc in Haiti, I asked for it to be sold at what was then $9 (dollars). One dollar was supposed to go for a Kreyòl edition. It never went. The royalties from Papa Doc went to pay the tuition for a young Haitian through university. My ambition is to be able to eventually sell my book on Haiti to Haitian students at a very low price. I would like to give them away. Students need to know their past. Few can afford books. We must help them. Printing and translating cost money. Bajeux, an exceptionally generous and talented person, translated Le Prix du Sang without cost. He plans a second edition with more photos.

A. I.: Do you find the Haitian literature a very rich one?

B.D.: There is so much in Haitian literature. I have a library—part of which I lost when I was expelled in 1963 along with my office and print shop—that speaks much about diversity of Haitian writers. I had the opportunity to know and interview some of those writers.

A. I.: Do you have some feedback on how Haitian communities in or outside of Haiti might react to Le Prix Du Sang?

B.D.: I am especially thrilled with the response to Le Prix du Sang and I hope in the second edition any errors or typos will be corrected. I have been encouraged by talks in Haiti, Boston and here in Florida with Haitian students. I realize they need the English edition, which I hope will be published soon.

A. I.: When do we expect to see the release of Tome II?

B.D.: Tome II—The Jean-Claude Duvalier years–is complete, and now it’s up to the translator—not an easy task.

A. I.: Do you also write fiction?

B.D.: My work is entirely non-fiction. I have a second son who writes fiction—not me. My eldest Haiti-born son, while a photographer covering Haiti, suffered a hand-wound in the 1987 election massacre in Ruelle Vaillant. He covered the last years of the Soviet Union and many big stories. We go often to Haiti and miss our grandchildren who live there.

A.I.: Are you also familiar with many Latin American writers?

B.D.: I am a fan of a lot of Latin American writers; some whom I’ve interviewed and known are Octavio Paz, Gabo—Gabriel García Marques, Carlos Fuentes etc. In Nicaragua I found poets. In El Salvador, the poets were all dead. I covered the Cuban rebellion and, after Hispaniola, Cuba is an old love. I definitely don’t like to hear all the stories about Fidel reaching eighty this year and that he is about to die. I am of the same age as Fidel, and I don’t intend to die soon.

A.I.: Does ideology play a role in your writings?

B. D.: I am not steered by ideology. I only possess a passion for the truth. And if we tell the truth about the past, we can tell the truth about the present.

A. I.: Thank you so much for taking some time out of your precious schedule to Speak to CSMS Magazine.

B.D.: Thank you for your interest. I hope soon to return and live in Haiti. Peace. Kenbe fèm.

Note: During the interview, Bernard Diederich made reference to Jean-Claude Bajeux, well known human rights activist, as the writer who translated The Price of Blood into French. As many of you may have already known, Bajeux died two years ago at the age of 79.