Jasmine Withlock

Special to CSMS Magazine

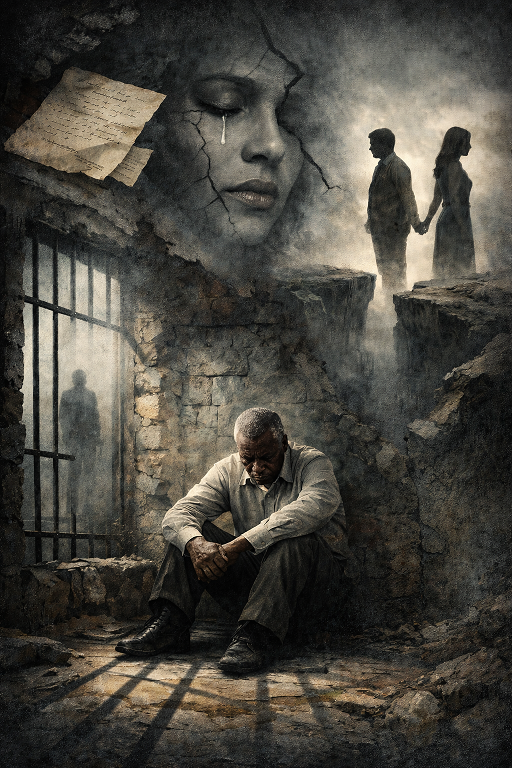

Not all prisons have walls.

Some are built slowly, almost tenderly, from the quiet accumulation of unspoken words. From the widening space between two once-intertwined lives. From the moment trust fractures and memory no longer feels safe. These prisons leave no visible scars, yet they reshape the landscape of the heart. In this reflection, we step beyond the iron bars of history and into the more elusive captivity of silence, distance, and betrayal — asking what it truly means to be free when the confinement is not political, but profoundly personal.

___________________________________________________________________

There are prisons made of steel.

And then there are prisons made of silence.

History teaches us how to recognize the first kind. We can see its walls. We can measure its cruelty. We can name its architects. Nelson Mandela survived such a prison — twenty-seven years confined behind bars forged by an unjust regime. When he walked free, he famously reflected that if he did not leave bitterness behind, he would remain imprisoned.

Steel did not defeat him.

Hatred did not own him.

Yet there is another kind of captivity — one less visible, more intimate, and in some ways more difficult to endure.

It is the prison guarded by silence, distance, and betrayal.

This prison does not restrict the body. It destabilizes the heart.

Silence is its first guard.

Not the peaceful silence of contemplation, but the silence that follows unspoken words. The silence of emotional withdrawal. The silence that communicates, “Your pain does not move me.” In political imprisonment, suffering is often witnessed. Letters are smuggled. Stories circulate. Support grows. But in relational silence, pain becomes private. It echoes without response. And without witness, suffering begins to distort the self.

Human beings are not designed to process emotional injury alone. We regulate ourselves through connection — through dialogue, recognition, validation. When silence replaces engagement, the mind becomes its own interrogator. Doubt creeps in. “Did I imagine the closeness? Was I misunderstood? Was I unseen all along?”

Silence does not shout. It erases.

Distance is the second guard.

Not merely physical miles, but emotional separation. The kind that grows gradually, almost imperceptibly. Two people may sit at the same table and yet inhabit different worlds. Shared language weakens. Shared meaning thins. What once felt instinctive now requires effort.

In long relationships, a psychological “we” forms — a shared identity constructed through memory, struggle, and hope. When distance expands, that “we” begins to fracture. Reconnection becomes difficult not because love vanished overnight, but because two individuals have evolved in different directions.

Mandela and Winnie endured radically different ordeals during his imprisonment. He was shaped by isolation and reflection. She was shaped by surveillance, confrontation, and political turbulence within the country. By the time freedom arrived, reunion revealed something painful: they had not merely endured separation — they had become different people.

Distance does not always destroy love. But it changes its terrain.

Betrayal is the third and most devastating guard.

Unlike silence, which withdraws, betrayal acts. It shatters trust actively. It does not merely create space — it contaminates memory. The wound is not inflicted by a faceless system, but by someone once trusted. And this is where the prison of the heart becomes most suffocating.

Political enemies operate from predictable opposition. Betrayal, however, collapses internal certainty. It forces painful questions: “How did I not see this? Was I naive? What else have I misjudged?”

Betrayal attacks three layers at once: trust in the other, trust in the relationship, and trust in oneself. The last is the most destabilizing. When self-trust falters, identity trembles.

Mandela could confront apartheid with moral clarity. He knew who he was in opposition to injustice. But personal betrayal offers no ideology to confront, no movement to mobilize, no speech to deliver. There is only grief — quiet, human, disorienting grief.

Political forgiveness can be principled. It can be anchored in vision, strategy, and collective good. Personal forgiveness is different. It requires vulnerability. It demands reopening wounds without guarantees. It risks further injury.

To forgive a regime is an act of moral strength.

To forgive intimate betrayal is an act of exposed humanity.

And sometimes even the strongest among us cannot fully access that vulnerability. That does not diminish greatness. It affirms it. Because only those capable of deep attachment are capable of deep pain.

The most haunting feature of this invisible prison is that its bars are internal. After betrayal, the mind replays scenes, reinterprets conversations, questions meanings. The guards become memories. The warden becomes fear. And unlike steel bars, these walls travel with us.

Yet here lies the deeper question: what ultimately keeps us imprisoned?

It is not silence alone. Not distance alone. Not even betrayal alone.

It is the decision — conscious or unconscious — to let those experiences redefine our capacity to love again.

Mandela walked out of Robben Island free because he refused to carry hatred forward. Emotional freedom may require a similar release — not of memory, not of discernment, but of fear.

The hardest prison to escape is not one made of steel.

It is the one where silence erodes belonging, distance fractures identity, and betrayal tempts us to retreat permanently from intimacy.

The true measure of freedom may not be whether we were wounded.

It may be whether we allow those wounds to determine the shape of our future connections.

In that sense, the deepest liberation is not political.

It is relational.

And it begins the moment we choose not to let pain close the gates of the heart.

Note: Jasmine Whitlock is a psychologist by trade. She wrote this piece especially for CSMS Magazine.

Also, see: Can Love Survive Without Respect?