By Ardain IsmaCSMS Magazine Staff WriterHeaven of Drums is a historical novel that describes Argentina’ s fight for independence—a war that lasted roughly ten year (from 1810 to 1820). What makes the story so intriguing is that it takes place during the tumultuous moments when the country was still struggling to find a national identity. It is also a story of love, involving three distinct figures that represented the Argentine’s society at that time: Manuel Belgrado, Caucasian and independence hero who leads the country to victory against the Spanish forces, but despite his open disdain for Blacks cannot help himself to fall in love with Maria Kumbá, a mulâtresse Creole and voodoo priestess who is not only a lover, but also an advisor to Belgrado. Maria is one of the principal heroes of the book along with Gregorio Rivas, a Mestizo—the product of an Indian woman and a rich Spanish businessman. Rivas also becomes Maria’s lover, but he is seriously disturbed by Maria’s commitment to staying with Belgrado, despite gross evidence that shows the general’s open hatred fro Blacks. In the fight against a common enemy, a tactical unity is created. It is unity based on lies and deception, where African slaves and Indians under false promises of freedom are being used as Chair à canon (cannon fodder) against well-armed British and Spanish troops. Against the odds, they fight with great stoicism, winning battles after battles in places where victory seems impossible to accomplish. But as victory is achieved and reality quickly sets in, promise of freedom is also quickly forgotten, for it was never foregrounded on the premise of social justice. One such glorious moment in the story that the author eloquently describes is the one that explains a British invasion in Buenos Aires with the complicity of the city’s Spanish authorities. Maria whose father—a white man—that never recognizes her, cannot bear the biggest humiliation of her life (pg.86). The author handles her pen well in this passage. “Hidden in the plaza market, she cried tears of shame watching that group of bleached-eyed soldiers….. Freed men and slaves formed militias gathered in [Maria’s] house to organize the forces in the barrio [of El Tambor]” (pg.86-87) Cielo de tambores is the Spanish title of the book, which may explain why the author uses the barrio of El Tambor to stage the spectacular entry of the Africans in the story. The story being told here is nothing new from countless stories that historians after historians have already put forward to describe the Americas in the early 19th century. What makes this story so unique, apart from the author’s eloquence in the writing, is the fact that it takes place in Argentina—a country that even most of its citizens would deny in a heartbeat the existence of people of African descent in their country, let alone their contribution to the country glorious moments in its history. There is an old joke that describes an Argentine as an Italian who speaks Spanish and who thinks he is British. Five years ago, the Miami Herald published an important article titled Black in Latin America: A shadow community, which portrayed the invisibility of Blacks in Latin America. According to the article, it is estimated that about 100 million people of African descent live throughout Latin America, with large concentrations in Brazil, Colombia, Venezuela, and Panama. But Blacks live all over Latin America since the start of the slave trade, including Argentina where historian Ysabelle Rennie explains why the black population in Argentina has substantially dwindled over the last century. Long after Argentina’s independence, many Blacks were still being held as slaves, which was not abolished until 1853. “Even after the official abolition of slavery, many blacks were still slaves and were granted manumission only by fighting in Argentina’s wars, serving disproportionately in the war of independence against Spanish rule and border wars against Paraguay from 1865 to 1870. Blacks were also granted their freedom if they joined the army, but they were deliberately placed on the front line and used as cannon fodder,” explains Ysabelle Rennie. The policy of bleaching the population is nothing new in Latin America, and officials have long resorted to all kinds of brutal tactics to achieve this shameful goal. Dominican fascist dictator Rafael Leonidas Trujillo introduced a policy called Blanco de la Tierra—something most historians call Blanco de la Mierda—where black women were distributed like toys to white immigrants, especially Germans in order to whiten the population. And when that was not enough to accomplish his goal, he went on a killing spree against the Haitians who had been living in perfect harmony with their fellow Dominicans for decades in the border areas. The killing had resulted into the massacre of thousands of Haitians in 1938, a subject that plays a major role in the Jacques Stephen Alexis’ 1956 gut wrenching novel Compère Général Soleil. In Cielo de tambores or Heaven of Drums, Ana Gloria Moya seems to have agreed with the fact of the disappearance of all Argentines blacks. In her epilogue, she throws in some passages filled with gloom and repressed resignation as she expresses her sincere sympathy toward all of them [who] were shamelessly exterminated, as if their blood was not important, their pain too cheap to inventory (page 187.) But the cry of the extermination of Blacks in Argentina may be too premature. According Maria Lamadrid, the head of Africa Vive, an organization that is fighting for the recognition of Blacks in Argentina, there are approximately one million people in Argentina who can claim to be of African descent. Of course, she was not talking about people with pitch-black skin color, which is now estimated at about 1% of the population. Census in 1778 showed that out of 24,363 of Buenos Aires residents, 7,236 of them, about 30 percent of the population, were Africans. The final year they considered Blacks as a category in the census was 1887, which showed a significant drop to about 2 percent. According to human rights activists, the government eliminated a black category in a deliberate attempt to promote an image of homogeneity. Another gut wrenching passage in the book is the one that describes the final years of Maria Kumba. Coming from being war hero, respected healer, believer of the African gods like Shango and Olorúm, lover of Gregorio Rivas—the Mestizo and the other hero of the book—Maria is now reduced to being a beggar. The author gives Rivas the opportunity to express himself in these terms. “Once in awhile news reaches me that she is begging near the cathedral, with a black shawl covering her face. I wish it were not true. I cannot reconcile the image of a beggar with my memory of that much-beloved woman. I was never able to learn for certain if she died or still remains alive. I dare not to go to look for her. I could not hold her gaze. I took away from her what she loved the most. I left her with her hands full of magic but empty of life. But I took it away from myself too.” (page 187) There is clearly a big difference with sexual pleasure and sexual happiness. Manuel Belgrado, national hero, did not think even remotely possible of the day that Maria Kumba would be in need of help, just like she was always there by his side, at his service (sexual or otherwise) during the darkest hours of the war in the mountains. She spent her final days as a panhandler in the dusty streets of Bueno Aires, in total obscurity, out of sight and out of mind of those who now gleefully claim that Argentina is a white nation built by white folk heroes like General Manuel Belgrado. This also reminds us of Sally Hemings—a charming mulâtresse— who bore several children for Thomas Jefferson. Jefferson, American independence hero, found the pretty mulatto girl so indispensable for his sexual pleasures that he traveled to Europe with her and later returned to America with her, but never awarded her freedom as she died a slave who was worth only 30 American dollars. Heaven of Drums is truly a book to read, a historical novel filled with intrigues that can resonate deep into the hearts of its readers. Ana Gloria Moya, the author, is awesomely skillful in developing her characters. This book reminds one of One hundred days of solitude by Gabriel Garcia Marquez. The author is the recipient of several literary awards, including the Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz prize for Heaven of Drums. Fairfield University professor Nick Hill translated the book into English. It can be purchased on www.amazon.com and other places on line.Also see Closed For Repairs: a book that offers a glimpse of life in urban CubaNote: The book was published by Connecticut based Curbstone Press. It is available almost everywhere, especially in all online bookstores. One can also visit the publisher’s website: www.curbstone.org for more info.

By Ardain IsmaCSMS Magazine Staff WriterHeaven of Drums is a historical novel that describes Argentina’ s fight for independence—a war that lasted roughly ten year (from 1810 to 1820). What makes the story so intriguing is that it takes place during the tumultuous moments when the country was still struggling to find a national identity. It is also a story of love, involving three distinct figures that represented the Argentine’s society at that time: Manuel Belgrado, Caucasian and independence hero who leads the country to victory against the Spanish forces, but despite his open disdain for Blacks cannot help himself to fall in love with Maria Kumbá, a mulâtresse Creole and voodoo priestess who is not only a lover, but also an advisor to Belgrado. Maria is one of the principal heroes of the book along with Gregorio Rivas, a Mestizo—the product of an Indian woman and a rich Spanish businessman. Rivas also becomes Maria’s lover, but he is seriously disturbed by Maria’s commitment to staying with Belgrado, despite gross evidence that shows the general’s open hatred fro Blacks. In the fight against a common enemy, a tactical unity is created. It is unity based on lies and deception, where African slaves and Indians under false promises of freedom are being used as Chair à canon (cannon fodder) against well-armed British and Spanish troops. Against the odds, they fight with great stoicism, winning battles after battles in places where victory seems impossible to accomplish. But as victory is achieved and reality quickly sets in, promise of freedom is also quickly forgotten, for it was never foregrounded on the premise of social justice. One such glorious moment in the story that the author eloquently describes is the one that explains a British invasion in Buenos Aires with the complicity of the city’s Spanish authorities. Maria whose father—a white man—that never recognizes her, cannot bear the biggest humiliation of her life (pg.86). The author handles her pen well in this passage. “Hidden in the plaza market, she cried tears of shame watching that group of bleached-eyed soldiers….. Freed men and slaves formed militias gathered in [Maria’s] house to organize the forces in the barrio [of El Tambor]” (pg.86-87) Cielo de tambores is the Spanish title of the book, which may explain why the author uses the barrio of El Tambor to stage the spectacular entry of the Africans in the story. The story being told here is nothing new from countless stories that historians after historians have already put forward to describe the Americas in the early 19th century. What makes this story so unique, apart from the author’s eloquence in the writing, is the fact that it takes place in Argentina—a country that even most of its citizens would deny in a heartbeat the existence of people of African descent in their country, let alone their contribution to the country glorious moments in its history. There is an old joke that describes an Argentine as an Italian who speaks Spanish and who thinks he is British. Five years ago, the Miami Herald published an important article titled Black in Latin America: A shadow community, which portrayed the invisibility of Blacks in Latin America. According to the article, it is estimated that about 100 million people of African descent live throughout Latin America, with large concentrations in Brazil, Colombia, Venezuela, and Panama. But Blacks live all over Latin America since the start of the slave trade, including Argentina where historian Ysabelle Rennie explains why the black population in Argentina has substantially dwindled over the last century. Long after Argentina’s independence, many Blacks were still being held as slaves, which was not abolished until 1853. “Even after the official abolition of slavery, many blacks were still slaves and were granted manumission only by fighting in Argentina’s wars, serving disproportionately in the war of independence against Spanish rule and border wars against Paraguay from 1865 to 1870. Blacks were also granted their freedom if they joined the army, but they were deliberately placed on the front line and used as cannon fodder,” explains Ysabelle Rennie. The policy of bleaching the population is nothing new in Latin America, and officials have long resorted to all kinds of brutal tactics to achieve this shameful goal. Dominican fascist dictator Rafael Leonidas Trujillo introduced a policy called Blanco de la Tierra—something most historians call Blanco de la Mierda—where black women were distributed like toys to white immigrants, especially Germans in order to whiten the population. And when that was not enough to accomplish his goal, he went on a killing spree against the Haitians who had been living in perfect harmony with their fellow Dominicans for decades in the border areas. The killing had resulted into the massacre of thousands of Haitians in 1938, a subject that plays a major role in the Jacques Stephen Alexis’ 1956 gut wrenching novel Compère Général Soleil. In Cielo de tambores or Heaven of Drums, Ana Gloria Moya seems to have agreed with the fact of the disappearance of all Argentines blacks. In her epilogue, she throws in some passages filled with gloom and repressed resignation as she expresses her sincere sympathy toward all of them [who] were shamelessly exterminated, as if their blood was not important, their pain too cheap to inventory (page 187.) But the cry of the extermination of Blacks in Argentina may be too premature. According Maria Lamadrid, the head of Africa Vive, an organization that is fighting for the recognition of Blacks in Argentina, there are approximately one million people in Argentina who can claim to be of African descent. Of course, she was not talking about people with pitch-black skin color, which is now estimated at about 1% of the population. Census in 1778 showed that out of 24,363 of Buenos Aires residents, 7,236 of them, about 30 percent of the population, were Africans. The final year they considered Blacks as a category in the census was 1887, which showed a significant drop to about 2 percent. According to human rights activists, the government eliminated a black category in a deliberate attempt to promote an image of homogeneity. Another gut wrenching passage in the book is the one that describes the final years of Maria Kumba. Coming from being war hero, respected healer, believer of the African gods like Shango and Olorúm, lover of Gregorio Rivas—the Mestizo and the other hero of the book—Maria is now reduced to being a beggar. The author gives Rivas the opportunity to express himself in these terms. “Once in awhile news reaches me that she is begging near the cathedral, with a black shawl covering her face. I wish it were not true. I cannot reconcile the image of a beggar with my memory of that much-beloved woman. I was never able to learn for certain if she died or still remains alive. I dare not to go to look for her. I could not hold her gaze. I took away from her what she loved the most. I left her with her hands full of magic but empty of life. But I took it away from myself too.” (page 187) There is clearly a big difference with sexual pleasure and sexual happiness. Manuel Belgrado, national hero, did not think even remotely possible of the day that Maria Kumba would be in need of help, just like she was always there by his side, at his service (sexual or otherwise) during the darkest hours of the war in the mountains. She spent her final days as a panhandler in the dusty streets of Bueno Aires, in total obscurity, out of sight and out of mind of those who now gleefully claim that Argentina is a white nation built by white folk heroes like General Manuel Belgrado. This also reminds us of Sally Hemings—a charming mulâtresse— who bore several children for Thomas Jefferson. Jefferson, American independence hero, found the pretty mulatto girl so indispensable for his sexual pleasures that he traveled to Europe with her and later returned to America with her, but never awarded her freedom as she died a slave who was worth only 30 American dollars. Heaven of Drums is truly a book to read, a historical novel filled with intrigues that can resonate deep into the hearts of its readers. Ana Gloria Moya, the author, is awesomely skillful in developing her characters. This book reminds one of One hundred days of solitude by Gabriel Garcia Marquez. The author is the recipient of several literary awards, including the Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz prize for Heaven of Drums. Fairfield University professor Nick Hill translated the book into English. It can be purchased on www.amazon.com and other places on line.Also see Closed For Repairs: a book that offers a glimpse of life in urban CubaNote: The book was published by Connecticut based Curbstone Press. It is available almost everywhere, especially in all online bookstores. One can also visit the publisher’s website: www.curbstone.org for more info.

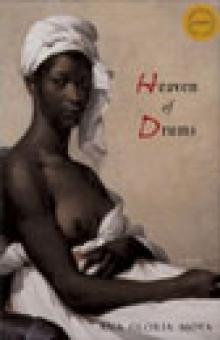

Heaven of Drums: A book that brings to light African presence in Argentina’s history

Comments are closed.

Thanks for taking the time to discuss this topic. I truly appreciate it. I’ll post a link of this post in my blog.

I agree with you and it also certainly seeing help lot of people.

Good to find out you back again. And again with an interesting posting.