By Ardain Isma

By Ardain Isma

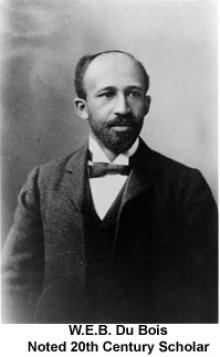

CSMS Magazine Staff WriterWritten by W.E.B. Dubois and published in the spring of 1903, The Souls of Black Folk has since been the pivotal point of reference for African American studies. One cannot understand the plight, the struggle, the dehumanized condition, the raw exploitation and the ultimate awakening of freedmen following the emancipation proclamation of 1865 without a tacit understanding of the Souls. This scholarly published manuscript is not a conventional thesis written through the prism of commercial success. Nor it is a gut-wrenching story evolved around a single subject. It is rather a synthesis, “a multifaceted, learned book addressed to an intelligence lay audience as a means of informing social and political action,” said Farah Jasmine Griffin, distinguished professor of English and Comparative Literature and African Studies at Columbia University. Many scholars agree that at the time it was written, the Souls was never intended to serve as the cornerstone of studies about the life of Black Americans in the United States. It is the complexity of the analyses and the author’s brilliance in his role as both “advocate and activist” that render the Souls the prestige it so deserves when it comes to understanding the history and philosophy of African Americans in the aftermath of the Civil War. In this interdisciplinary understanding of freedmen life in the latter part of the 19th century and at the dawn of the 20th century, Dubois uses a metaphorical theme that he calls the Veil to clarify and simplify the wholly distinction—lifestyle, that is—between Black and White in America. Beneath the Veil lies the vast majority of newly freed slaves who yearn for the poetic justice they wholeheartedly believe they deserve after they were forcefully made to live in subhuman conditions for more than 300 years. But outside of the Veil and within it also lives what Dubois calls “the Talented Tenth,” which he describes as the trained few that constitutes a leadership—a vanguard—of racial uplifting. Here, Dubois introduces the concept of “double consciousness” in which he defines the psychology of African Americans’ inner struggle for national identity—an American identity still clouted in the dark alleys inside the Veil, in the mounting barriers designed to forever keeping them [the Blacks] pin down beneath the Veil and in the dubiousness of the educated elite who can’t seem to find pride, happiness and consolation within his own roots, but rather seeks righteousness and social empowerment only through the eyes of White America. Dubois takes aim at this “Talented Tenth” who feels trapped in his own struggle for acceptance and who can only measure self-worth, beauty and intelligence “through standards set by others.” While halfheartedly claiming the elite to be the representative of racial uplifting, later in his life he rejected this theory.As an analogical stew, Dubois’s theoretical prose has been described like an amalgam of pertinently conceptualized analysis “shaped by biblical and mythological narrative, metaphor and allusion.” More than a hundred years after it was published, The Souls of Black Folk remains a paradigmatic key that contemporary thinkers and other academics cannot overlook in today’s discourse on race relation in America. In the first chapter titled Of Our Spiritual Strivings, Dubois depicts a romantic, but yet sorrowful, recollection of his childhood—his first encounter with racism at his schoolhouse during a card exchange between pupils where a girl refused to take his card, rejecting him “peremptorily, with a glance.” That encounter and the subsequent rejection that followed quickly enshrined in him “a certain suddenness that I was different from the others; or like, mayhap, in heart in life and longing, but shout out from their world by a vast veil.” Since that unexpected awareness, he nurtured no desire to remove the veil or to “creep through,” and held in common contempt all those who live above and beyond the veil “in a region of blue sky and wandering shadows.” The young Dubois, still unaware of the complexity of life—its nightmarish elements—was full of hope, and when he was the first ahead of his class in academic exams or in foot races, his contempt grew even more into an awesomely self-reassurance only to be faded like the crepuscule at dusk as years passed and as he began to realize that “the worlds I longed for, and all their dazzling opportunities, were theirs, not mine.”William Edward Burghardt Dubois grew up in Great Barrington, Massachusetts, where he was born in 1868. It was the year Congress passed the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution, granting the freed slaves citizenship and guaranteeing their civil rights. In the industrial north, slavery had long been a thing of the past for it could not be, just like in the South, a lucrative enterprise. However, racial inequality never disappeared. Blacks and other minorities constituted the disenfranchised population condemned to live in the fringe of society. Convinced his life would forever be pent inside the veil, he grew steadily disillusioned, especially as he watched with weeping eyes the youth of other black boys in his town—resigned and aloof—sunk into “tasteless sycophancy or silent hatred of the pale world about them and the mocking distrust of everything white.” According to Dubois, understanding the history of American Negro is to understand the history of a strife—an everlasting longing to conquer his “self-conscious manhood, to merge his double self into a better and truer self.” The author quickly clarifies the merging of the Negro double self in which he wishes to lose neither his old self nor does he wish to Africanize America “for America has too much to teach the world;” nor does the Negro wish to bleach his soul “in a flood of white Americanism, for the Negro has a message for the world. That is, he wants to make the world know that it is possible to be both a Negro and an American without being shunned, “cursed or spit upon by his fellows [and] without having the doors of Opportunities closed roughly in his face.” But the issue of African American patriotism has never faded, and more than 150 years after the abolition of slavery the horror of servitude still hunts European Americans, creating an unspoken self-inherited, self-conscious guilt that unless justice is done, the instilled guilt may last forver—and for all practical purposes it never will in its fullest extent. Heretofore, African Americans will never truly be Americans in the eyes of those whose ancestors have perpetrated the most hideous crime humanity has ever registered. In the shadow of this conceptualized paradox, Dubois acknowledges that not everyone in White America shared the vexing idea of marginalizing the newly freedmen and freedwomen. He gleefully and honestly points out the names of several generals in the Union army whose efforts paved the way for the military government in Washington to open confiscated lands to the cultivation of the fugitives. Among them were General Dixon for his action at Fortress Monroe, General Banks in Louisiana, Colonel Eaton, the superintendent of Tennessee and Arkansas and General Saxton of South Carolina. They all contributed in some ways to the amelioration of the lives of thousands of former slaves by handing over thousands of seized estates to them. Dubois also points out the fifty or more social organizations like the American Missionary Association, the national Freedmen’s Relief Association, the American Freedmen Union, the Western Freedmen’s Aid Commission and more…. which were sending many relief supplies like clothes, books, money and teachers to the South. They all were founded by northern abolitionists who had been waiting in the wing for the slightest opportunity to act; and that opportunity aroused immediately after the liberating army entered Virginia and Tennessee. Thousands of fugitives moved in droves to seek shelter behind the Union army lines. As Dubois describes this frightening scene:They came at night, when the flickering campfires shone like vast unsteady stars along the black horizon. Old men and thin, with gray and tufted hair, women with frightening eyes [and] their hungry children…a horde of starving vagabonds, homeless, helpless, and pitiable in their dark distress. Above all, Dubois seems to take pride in the creation of the Bureau of Freedmen—something he calls “one of the most singular and interesting of the attempts made by a great nation to grapple with vast problems of race and social conditions.” However, all these seemingly great efforts and good intentions faded as the war ended and Washington’s strategic interest has shifted from appeasing the deprived Negro population yearning for justice to appeasing the “recalcitrant South” and its camouflage agendas, which resulted to the painful reversal of the earlier gains for the Negroes. These setbacks along with the cooptation of many of the “Talented Tenth”, chief among them Booker T. Washington who forfeited the Negro’s rights to social and racial equality in favor of economic opportunity, Dubois grew evermore disillusioned. But his vision as a thinker and his ability to flex his puckish wit has made him a menace to the State. For years, he was forced to live under house arrest forbidden to leave the country as he was barred to travel to Paris in 1956 to lead the first congress of Black writers and artists organized by Présence Africaine. Doctor Jean Price Mars of Haiti had to take his place. It is strongly recommended to revisit this book at a time America is trying to redefine itself. It could be a guide quintessential to understanding what has really changed or has not changed from 1868 to 2008. As millions of African Americans still wallow in poverty, and entrenched institutions of higher learning still shut upon their faces, one wonders how long will it take for the poetic justice missed in 1868 to finally find its way into the lives of millions of still disenfranchised individuals longing and yearning for equal opportunities and justice for all.Note: Dr. Ardain Isma is the chief editor for CSMS Magazine and the executive director of the Center For Strategic And Multicultural Studies. He also teaches Cross-Cultural Studies at Nova Southeastern University. He is a novelist and the author of several essays on multiculturalism and Caribbean politics. He may be reached at publisher@csmsmagazine.org .Also see The 1956 Paris CongressA Chinese Princess like no other (Part I) The last time I saw ElodieCoping with holiday stress Best tips for emerging writersCommercial success or literary lust: the dilemma facing many of our promising authorsPaul Laraque, internationally renowned Haitian poet and militant, has died

Thank you for another amazing entry. Where else could anybody get that kind of information in such a amazing way of presentation.