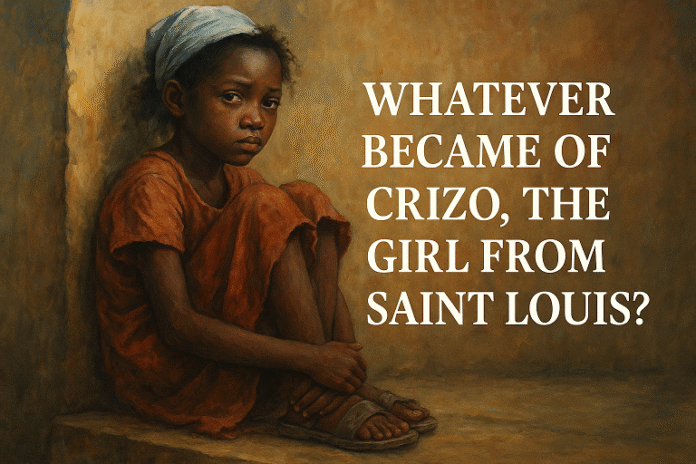

A haunting true story that reminds us why the fight for every child’s dignity must never stop.

Ardain Isma

CSMS Magazine

Editor’s Note (2025 Reprint):

I first published this story in 2013, long before *The Cry of a Lone Bird* came into existence. Yet, as I revisit Crizo’s memory today, I see how her silent suffering continues to echo in the lives of countless children living in servitude across Haiti and beyond. This piece is being republished not as a mere recollection, but as a call to conscience—a plea to remember the invisible children whose cries still go unheard.

____________________________________________________________________

She was the girl next door, the little restavèk everyone overlooked. A shy, slight figure who walked with an unsteady gait, her ragged dress floating in the tropical wind, her cow-skin sandals clapping underfoot like hooves on gravel. She was tall and slim, the color of jet-black coffee, with an innocent, oval face that seemed perpetually veiled by the shadow of her existence. She was always sad, but few ever noticed her profound solitude.

Crizo lived on the fringe of everything mainstream. In her own home, she was forbidden from sitting at or near the dining table. A tiny, low wooden chair, glued to the corner of the room, was her designated seat—and only after she had finished every last chore.

At dusk, as the sun sank behind the thick gray clouds and darkness engulfed Saint Louis du Nord, Crizo would retreat to that low chair, swarmed by leeches that stung her tired little body. She never dared to cry, wail, or complain. Her legs would grow numb, and she would feel neither pain nor relief until she slowly drifted to her makeshift bed—a nat, a mat of dried banana fronds, rolled onto the floor and covered by a flimsy sheet. A Spanish moss pillow without a case was stuffed beneath her head. There, she spent the night lurching sideways until dawn came to her rescue, and she would rise into the same fog of a nightmarish existence, as hopeless as the day before.

I never knew her age, but Crizo was undoubtedly the youngest soul in a household of five. There was Josélia, an oversized woman whose cheeks bulged from chewing tobacco powder; Monsieur Norméius, her husband, a fat-bellied politician who served as the Justice of the Peace in town, yet whose contempt for the wretched ran so deep he was blind to the daily injustice unfolding within his own home.

The couple had two daughters. Pierreline, a young woman with a golden tan in her early twenties, had yet to learn how to pick up a broom to sweep her own front porch—the very spot where she made uncontrolled love with her elusive boyfriend under the starry Saint Louis sky. Neighborhood gossip labeled him a playboy aficionado, the greatest gigolo from Vertus, the northernmost part of town.

The other daughter was Inata, an aloof figure lost in a surreal world of French movie stars and the frenetic dreams of an uptown girl—a petite bourgeoisie oblivious to the crumbling reality around her. Wrapped in the tan of creamy coffee, Inata was the elder, yet it was Crizo, the youngest by far, who executed every daily necessity. She carried water jugs on her head from the nearby creek of Ti-Rivyè, cleaned, washed, and cooked.

Over time, Crizo learned to tolerate her dehumanizing condition. She became skillful at concealing the hellish pain dwelling inside her, enduring the blows, kicks, and blatant humiliation without ever sharing her profound suffering.

Each morning, while other children headed south to school in starched, ironed uniforms, Crizo walked in the opposite direction toward the Ti-Rivyè marketplace, draped in rags with a dirty head-cloth wrapped around her uncombed hair. As the morning sun rose over her jet-black face, no trace of happiness could be detected—only a broad, disengaged smile.

Her mind may have found a way to cope, but her body was not so forgiving. By her late teens, Crizo was utterly disfigured, her body aged beyond recognition. Deemed useless, she was forced to return to her biological parents, people she barely knew, who had given her away when she was only five.

And so, Crizo vanished into the world of the unknown on a December morning, on the eve of Noël, just as Santa prepared to command his sleigh full of presents for another trip into town. Not a single tear was shed as her weather-beaten body treaded down the rocky riverbed of La Rivière des Barres, taking the sugar-sand trail through the valley of Forge to reach a relative’s hut deep in a mountain gorge near the village of Casalie.

Those of us who knew her were deeply saddened by her departure. But like children everywhere, unable to grasp the complex problems of society, we let Crizo’s story sluggishly fade from our minds until the little restavèk plunged into oblivion.

Yet, though many years have passed, Crizo’s silhouette still flashes across my mind. I wonder how different life might have been had she been given the opportunity to live productively. Her wasted mind, body, and soul could have been so useful to our motherland, Haiti. Who knows?

How many Crizos are we losing every day?

Note: Restavèk is a child living in servitude, like a modern-day slave.

Crizo’s story is not just about the past—it is the mirror of our collective failure and the hope of our awakening. As long as there is a child who sleeps in fear, the cry of a lone bird will echo through our conscience.

Note: Dr. Ardain Isma is editor-in-chief of CSMS Magazine. He is an essayist and novelist. You can purchase his latest novel, The Cry of a Lone Bird, here.

Note: Dr. Ardain Isma is editor-in-chief of CSMS Magazine. He is an essayist and novelist. You can purchase his latest novel, The Cry of a Lone Bird, here.