CSMS Magazine

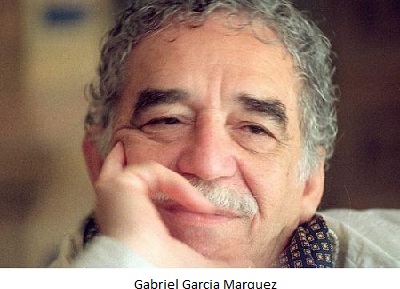

Gabriel Garcia Marquez, one of the twentieth century greatest writers, passed on this afternoon. Marquez is the author of “One Hundred Years of Solitude,” a novel that sold more than 50 million copies and translated in countless languages. He went on to produce a multitude of dazzling masterpieces, including “The General and His Labyrinths,” a tribute to Simon Bolivar, “Love in the Time of Cholera” etc..

I am personally fascinated by Marquez’s style of writing, his clearly defined position in the literary spectrum for having been a diehard proponent of social justice, his satirical ways of trivializing in sarcastic literary fashion the highest layers of recalcitrant bourgeoisies, and his indescribable wittedness.

Marquez was often called the most significant Spanish-language author since Miguel de Cervantes, the 16th-century author of “Don Quixote.” This assertion was confirmed by Chilean poet Pablo Neruda who admitted in an interview with Time. Few writers in Latin America have come close to holding such prestige. Among them, we find Neruda himself, Alejo Carpentier of Cuba and Eduardo Galeano of Uruguay. Had he lived, Jacques Stephen Alexis could have reached this high echelon, but the Creole fascists in Haiti had silenced his voice.

Because of reactionary politics and the appalling nature of the violence usually associated with it, Marquez was forced to leave his native Colombia to settle in Havana, where he spent many of his years.

Gabriel Garcia Marquez was born in the town of Aracataca, a sleepy town in Northern Colombia. Aracataca has always been the center of Marquez’s inspiration. The fictional town of Macondo beautifully described in “One Hundred Years of Solitude” published in 1967 was a reference to Aracataca. The town was also at center of other masterpieces as his novella “Leaf Storm” and the novel “In Evil Hour.”

“I feel Latin American from whatever country, but I have never renounced the nostalgia of my homeland: Aracataca, to which I returned one day and discovered that between reality and nostalgia was the raw material for my work.” In this passage, Marquez seems to have heeded the words of Jean Ferrat, “Nul ne guérit de son enfance.” No one can forever shun his childhood. Marquez was 87.

He has lived beyond his physical sate of being. Through his words, Marquez lives on—and for eternity.