CSMS Magazine

When I was a child, I used to enjoy visiting my grandmother every weekend. It was a way to escape the rigid parental surveillance. Grandma lived in a cottage on the eastern edge of Anwodo, a tiny village located just one kilometer away from the northern tip of the town of Saint Louis du Nord, in Haiti’s Northwest province. The village was modestly populated. There were few cottages roofed by thatch disproportionately tied together by a web of pathways. To get to Anwodo from my house, I had to hike over a goat-grazed hillside on top of which I could look down to contemplate with awe the fat banana leaves that canopied the vegetable garden, stretching all the way to the back gate of my parents’ courtyard. There, on top of the hill, I always felt a sense of dominance, a feeling of liberation. I could breathe a sigh of relief.

The hilltop marked the official start of Anwodo which by the way means over the hill in Creole. It was the little place where everyone knew your name, where everyone was related to the same bloodline. A pebbly trail ran through the village, which connected it to the picturesque valley of Ti-Rivyè, on its eastern fringe. All along the trail were small houses inhabited by relatives. An intricacy of lime green vegetables adorned their courtyards. I had to stop in front of every one of them to greet a great-uncle, a cousin, or a stranger coming down from the mountain on its way to the marketplace near downtown Saint Louis.

The frequent stops pinned down my progression, and it was joie de vivre when I finally reached the giant mango john tree where the trail branched off to create an alternate that led to the step-stones of my grandma’s front porch. Two lines of lima beans poles backed by layers of okras and pigeon beans trees festooned the garland entrance. Already, I could hear grandma’s strong filtered voice reverberated near the outdoor kitchen. Upon spotting my silhouette pushing toward the courtyard, she would edge closer to meet me halfway.

“Dinco,” she would scream, bursting out laughing—hands on the hips, quite assured of herself. Her bronze face would radiate in the sunglow. My both arms outstretched, I would take a nosedive into her long calico garment, burying my head there. Tall as she was, she would bend her head down –her neck stretching like a Chinese goose—to strait up my little creamy face and start stroking my kinky hair. Soon, she would pat me on the back and set me free like a released bird to go joining my little cousins playing around the courtyard.

At first, we would congregate under a humongous mangfransik mango tree, talking about our latest ordeals from school. Next, we would direct our attention to an overgrown walkway that led to the bed of a shallow ravine where we would then go to catch crawfish. The soft fragrant scent of wild citronellas fumed the air, and on both banks of the ravine trail, cashew apple trees filled with nuts attracted my attention. I would stone, snap, snatch them off the ground to later grill them over a cook-fire.

My grandma’s place was the best of all, at least to me. It was the best of time, too. However, there was this young boy named Daniel, looking frail and tall, who was not part of the family, but who was always with us, teaching us how to better catch the fish. He had reddish hair, like that on top of maize stalks. He was usually shirtless and wore dark trousers rolled up to his knees. He knew all the leaves in the bushes. He had an acute awareness of the role of each plant—what it was good or bad for. But he didn’t know how to read or write. He lived in a tiny cottage in the hollow of Bwa Chandèl, a fringe community over the next hill. He was being raised by a single parent, his mother, a lady named Lavanie who was a roadside bread seller. Her meager income was just enough to keep her family from falling victim of starvation, obviously not sufficient to purchase the necessary supplies to send her kids to school.

My cousins would make fun of Daniel, but he never showed any sign of anger. He simply enjoyed being among us. Later, the more I grew older, the less I visited my grandmother, as schools obligations took center-stage. Consequently, the less I saw Daniel. But from time to time, he would come to see me, all the way to my house in town, his hands holding a plastic bag filled with my favorite mango menvil.

I would take him under an almond tree in the courtyard. There, we would talk until the afternoon sun began to slant, and he would head east toward the hilltop, back to his home. One day, Daniel came to visit and I took him for a walk down the neighborhood. It was that day I discovered that he had the same taste all city boys possessed when it came to flirting with girls. Few houses down, we met a chubby girl named Foufoune, who wore red madras, standing on the balcony of her parents’ home. I waved, and she grinned. Daniel instead threw kisses to her. “Be careful,” I said, “Her grandma is a reputed werewolf,” I added. Daniel did not seem to be afraid of that. Foufoune of course ignored his kisses. “Hey Dinco, your friend is too fresh,” she uttered.

So, we kept on walking and soon we ran into a group of girls—all of them were so pretty like a flock of dove ready to go on their first morning fly. One of them was my cousin Constance with the skin tone of a milky coffee, who had on a loose flowery garment. An orange foulard wrapped around her neck. She was stylish and full of pride. She moved away from the pack and walked over a croton edge near the front porch of her home. Her friend Annicette—a tall young woman with squinting eyes courted by all neighborhood lads—quickly followed her. My friend and I strolled toward them. We chatted for a while, but I kept watching Daniel’s demeanor each time Constance weighed into the conversation. He seemed coy by her buck-hole cheeks and sexy lips coated in red lipsticks.

When it was time to depart, the girls walked us back to my mother’s front door, and we hugged each other goodbye. Then I walked Daniel all the way to the hilltop, and I stood there watching his silhouette fading into the horizon. This was the last time I saw Daniel, the boy who was kind and humble, who would bow to greet an adult, who knew all the leaves in the wilderness. What a great medical doctor he could have been? On my several trips to Haiti, I searched for him, but no one seemed to know of whatever happened.

Human intelligence is a country’s best resource. Yet, we are wasting it every day in Haiti. I long for the day when every Haitian child would get the opportunity to receive an education. The country as a whole will surely benefit from it.

Note: Mango John, mangfransik, menvil are some of the varieties of mangoes in the tropic.

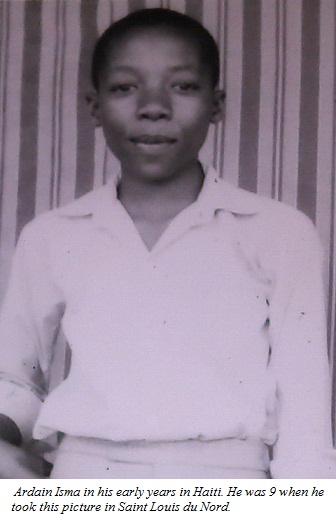

Dr. Ardain Isma is editor-in-chief of CSMS Magazine. He teaches Cross-Cultural Studies at the University of North Florida (UNF). He is a scholar as well as a novelist. He may be reached at:publisher@csmsmagazine.org