Jacob Davis

CSMS Magazine

Some novels arrive with noise.

Others arrive with necessity.

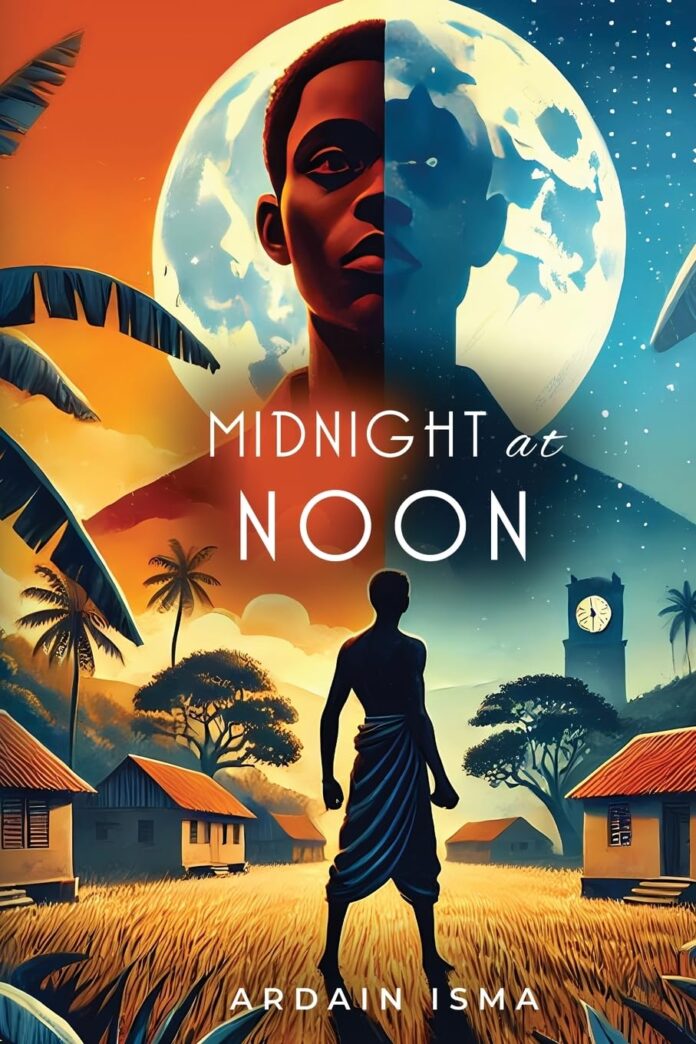

Midnight at Noon belongs to the second category—the kind of book that does not ask for attention but demands remembrance. It is a novel written against erasure, against the quiet violence of forgetting, and against the convenient amnesia that often surrounds histories deemed uncomfortable, inconvenient, or too painful to sustain.

At the center of this moral reckoning stands Odilon, a peasant boy from rural Haiti—uneducated in the formal sense, yet profoundly literate in suffering, dignity, and moral choice. Readers have called him “Haiti’s every man,” and the description holds true: Odilon is not a hero by design, but by circumstance, conscience, and refusal.

Odilon and the Cost of Forgetting

The title itself—Midnight at Noon—is an indictment. Midnight, the hour of darkness, occurring at noon, the height of daylight. It names a world where truth exists in plain sight yet remains unseen. Where injustice is known, named, and normalized.

Odilon inhabits this contradiction. He lives in a landscape of lush beauty that masks deprivation, where power and poverty collide daily, and where silence is often mistaken for survival. His life is not shaped by ideology, but by labor, kinship, and the fragile hope that decency might still matter.

That fragile hope is shattered when his brother is wrongfully arrested and killed under a brutal dictatorship. This loss is not a narrative device; it is the moral rupture of the novel. From that moment on, Odilon is forced into a decision no ordinary person should have to make: submit to fear, or accept the cost of resistance.

The Human Face of Class Struggle

One of the novel’s most striking achievements is its insistence that political violence is never abstract. It enters homes. It rearranges families. It leaves behind widows, orphans, and men like Odilon—who did not seek confrontation, yet cannot unsee what has been done.

Odilon does not rise as a revolutionary icon. He rises as a brother, a son, a peasant who understands—perhaps more clearly than those in power—that dignity cannot survive indefinitely under humiliation.

Through him, Midnight at Noon renders class struggle not as rhetoric, but as lived experience. Hunger is not symbolic. Fear is not theoretical. Courage is not guaranteed.

Exile Without Leaving Home

Exile in Midnight at Noon is not always geographical. For Odilon, it is the slow realization that the moral order he trusted no longer exists. His land is familiar, yet estranged. Authority figures—embodied in the ruthless Chief Anakreyon—no longer protect but prey.

This internal exile is one of the novel’s most devastating insights: one can be displaced without ever crossing a border. Odilon becomes a stranger in his own country, forced to navigate a system designed to silence him.

Yet the novel never strips him of agency. His resistance is not loud, but resolute. It grows from grief into resolve, from fear into responsibility. In Odilon’s journey, the novel honors the countless unnamed men and women who resisted not because they believed they would win—but because surrender was no longer possible.

A Refusal to Romanticize Resistance

Midnight at Noon does not romanticize revolution. It understands its cost. Odilon’s courage is neither glamorous nor safe. It is marked by doubt, loss, and the knowledge that justice rarely arrives cleanly.

What the novel offers instead is something rarer: moral heroism without illusion. Odilon does not fight because victory is assured. He fights because silence has become a form of complicity.

In doing so, he becomes emblematic—not exceptional. He stands for those whose names do not enter textbooks, yet whose quiet defiance sustains the moral memory of a people.

Why Odilon—and This Novel—Still Matter

In an age that favors spectacle over substance, Midnight at Noon insists on attention rather than urgency. Through Odilon, it reminds us that history is not only shaped by leaders and slogans, but by ordinary individuals who refuse to disappear quietly.

The novel matters because forgetting is not passive. It is a choice.

And remembering—through characters like Odilon—is an act of moral courage.

This is not a book that asks, Did you enjoy it?

It asks, What do we owe those who resisted when silence was safer?

That question, once embodied in Odilon, does not fade easily.

Also see: Midnight at Noon – A Must-Read Story of Resistance and Resilience