At a time when the Haitian struggle seems to have reached an impasse, it is quintessential to revisiting these remarks made by Dr. Ardain Isma back in 2009. In the face of a growing vulgarism in Haitian politics, many leftist organizations, which have long been considered to be the popular vanguard against the return of Duvalierism, appeared to have melted away. God only knows where they are, now. Many of their leaders have simply retired or passed on, for no one will live forever.

At a time when the Haitian struggle seems to have reached an impasse, it is quintessential to revisiting these remarks made by Dr. Ardain Isma back in 2009. In the face of a growing vulgarism in Haitian politics, many leftist organizations, which have long been considered to be the popular vanguard against the return of Duvalierism, appeared to have melted away. God only knows where they are, now. Many of their leaders have simply retired or passed on, for no one will live forever.

In the wake of Midnight at Noon, this gut wrenching novel by Ardain, we feel compelled to take upon ourselves the role of reeducating our readers on Haiti’s social contradictions and the historic mission of La Gauche (The Haitian Left) to remain true to its creed: accompanying the masses all the way to victory. In paying tribute to the heroes of PUCH, Ardain warns of “petty bourgeois aspirations,” the cancerous cell that continues to eat away Haitian dignity and, by extension, Haitian independence.

__________________________________________________________________

Forty years after the 1969 PUCH initiative: what is now left for la gauche haitienne?

By Ardain Isma

CSMS Magazine staff writer

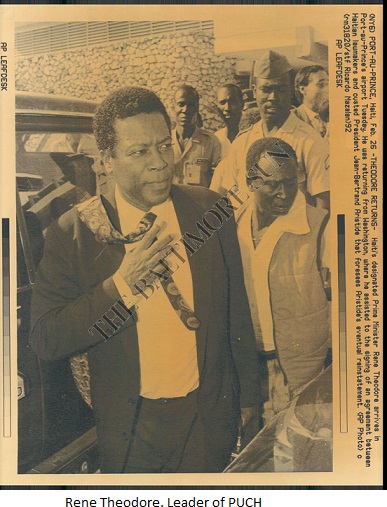

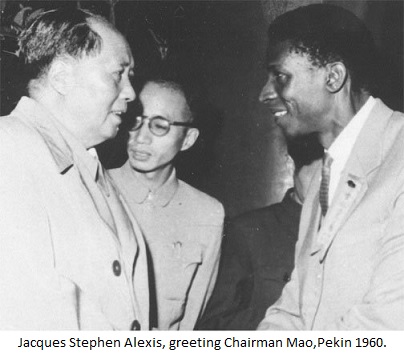

As we are nearing the end of 2009, a memorable event has almost gone unnoticed. This year marks the fortieth anniversary of the historic merge between two Marxist organizations in Haiti: Parti de l’ Union des Démocrates Haitiens (PUDA) formerly known as Parti Populaire de Libération National (PPLN) founded in 1954 in close collaboration with Jean-Jacques Dessalines Ambroise and Parti d’ Entente Populaire (PEP) founded by Jacques Stephen Alexis in 1959. In January of 1969, these two organizations joined forces in a union that gave birth to Parti Unifié des Communistes Haitiens (PUCH). The coming of PUCH gave great encouragement to an important layer within the petite-bourgeoisie for the founding fathers were almost exclusively from the middle class with a significant number from the grande bourgeoisie overwhelmingly mulattoes. But it also strengthened the hands of the Creole fascists in Haiti. So the radicalized Marxists, enigmatic in their glory, were going to face one of the most ferocious regimes in the country’s history.

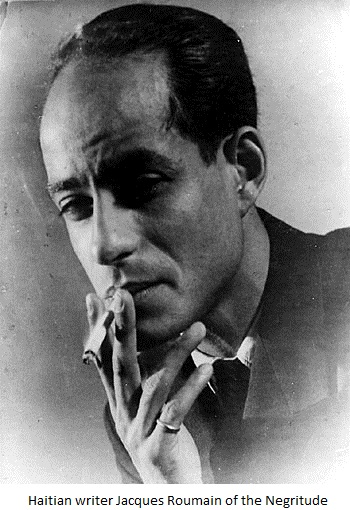

Heroically, they fought and died with the hope of triggering an awakening within the disenfranchised masses. Historic by its nature, for it was the first time since independence and also the first time since the creation of the HCP (the old Haitian Communist Party) in 1934 by Jacques Roumain and friends that a genuine movement was underway to bring to bear democratic governance in Haiti. Although Marxists, their aim—at least at the initial phase—was never to impose on society a proletarian dictatorship crafted under a dogmatic Marxism. In the absence of an organized working class, they believed, no proletarian revolution was possible; and that only a strategic alliance with a certain “patriotic” sector of the upper class could help further their cause at achieving the emergence of a working class—quintessential phase toward the fulfillment of a socialist state. So, their struggle was none other than a national liberation one viewed through the prism of the Cuban model with a Leninist tan.

Couldn’t it be different for Marxist militants of that era?

The late fifties, by all account, were considered as the precursor of the next decade (the sixties) historically called the “revolutionary decade,” particularly in Sub-Saharan Africa, Southeast Asia and the Caribbean. In 1959, the Cuban revolutionaries overthrew Fulguencio Batista and triumphantly pushed their way into Havana with their Kalashnikovs wrapped around their necks. In the DR (Dominican Republic), under pressure from a rising Marxist militancy and other social layers of society, bloody dictator Rafael Leonidas Trujillo was forced to choose Joaquin Balaguer as figurehead president. But in Haiti, Papa Doc—the God Father of Creole fascism—was in full ascendance of power, putting in place one of the most sadistic regimes on earth with the help of a completely dazed military hierarchy, the dinosaur-feudal/wealthy landowners, a confused sector of the bourgeoisie comprador along with some dubious elements of the middle class—overwhelmingly blacks—hungry for power and wealth with an acute aim at creating a bourgeoisie bureaucratique using pigmentation as their creed to justify their vulgar opportunisms.

The late fifties, by all account, were considered as the precursor of the next decade (the sixties) historically called the “revolutionary decade,” particularly in Sub-Saharan Africa, Southeast Asia and the Caribbean. In 1959, the Cuban revolutionaries overthrew Fulguencio Batista and triumphantly pushed their way into Havana with their Kalashnikovs wrapped around their necks. In the DR (Dominican Republic), under pressure from a rising Marxist militancy and other social layers of society, bloody dictator Rafael Leonidas Trujillo was forced to choose Joaquin Balaguer as figurehead president. But in Haiti, Papa Doc—the God Father of Creole fascism—was in full ascendance of power, putting in place one of the most sadistic regimes on earth with the help of a completely dazed military hierarchy, the dinosaur-feudal/wealthy landowners, a confused sector of the bourgeoisie comprador along with some dubious elements of the middle class—overwhelmingly blacks—hungry for power and wealth with an acute aim at creating a bourgeoisie bureaucratique using pigmentation as their creed to justify their vulgar opportunisms.

Haiti then was in a complete state of siege reminiscent to the one that preceded the US occupation in 1915. Papa Doc, a wicked sly who specialized in political cunning, presented himself as the messiah of the last hour on a mission to rescue Haiti from its failed-state condition inherited from its 19th century neo-colonialism and semi-feudalism. The crisis had exacerbated during the years following the Second World War when Haiti seemed powerless at resolving its internal contradictions. In his infamous inaugural speech on that sad day of October 22, 1957, Papa Doc claimed his “awesome” goal was that “I want by the end of my term that hope would become reality for I will dedicate every day [of my presidency] to thinking of [the people] humane condition as well as showing my genuine affection.” Little did anyone know that what Haiti was witnessing was the making of a sneaky monster and the foundation of a dynasty stemmed from noirism (a reverse form of racism) built around Papadocism, the doctrine that Papa Doc would later create. The results were total polarization of the Haitian society, the unleashing of his tonton macoutes on the most wretched layer of the population, and a nose dive into abject poverty. Although elected for 6 years in a one-term only mandate, by the summer of 1961, Papa Doc had already tightened his grip on power, slaughtered scores of his opponents, sent thousands into exile and self-declared president for life. The stage was set for an open-ended dynasty that only a well coordinated effort by genuine patriotic Haitians with the use of whatever means necessary could do away with the fascist regime.

Facing such peculiar dilemma, the revolutionary forces in Haiti—though limited in their range of options—felt dangerously compelled to offer a revolutionary alternative to the Haitian masses. To do otherwise, they thought, it would have amounted to a total subjugation of the masses by Papa Doc and his henchmen and it would also have given the fascist regime a free pass to ride unopposed down the highway of death and destruction. Roger Aubourg, young Haitian poet with puckish wit and a distinguish intellect once stated: “The use of any means, including trenched warfare to eradicate evil doers such as those the masses of Haiti face daily is morally, politically and holy justified.” Of course, Aubourg eventually became victim of the Creole fascists when he mysteriously disappeared in a hot summer night of 1964. Like many others, his body was never recovered. He was only 24. If the beauty always rests in the eyes of the beholder, so too is the ugliness. And the ugliness, here, was unbearable.

A strategic and regrettable blunder

No one holds the key to the revolution, and only gut wrenching individuals lead revolutions to successful conclusions. Our forefathers in 1804 were a prime example. Here, in CSMS Magazine, we’re not interested in a sterile discussion about the militarist and maximalist attitude of the leaders of PUCH, who tried and failed with unimaginable consequences of what seemed to be a well justifying attempt to rid the country of fascism. Their military mishaps both in strategy and in tactic coupled with a bizarre and quirky mix of short-sidedness and a profound revolutionary conviction led to their miserable failure. “The dilemma of bringing Marxism-Leninism to the masses does not only rest with the social origin of the PUCH leaders [overwhelmingly mulattoes from high-middle to the highest echelon], but it also rests in many other reasons that constituted a serious hindrance to the advancement of the struggle,” notes Marc-Arthur Fils-Aimé in his essay on Tribute to the PUCH militants: forty years later. (Voir Honneur aux camarades du PUCH : Quarante ans après )

No one holds the key to the revolution, and only gut wrenching individuals lead revolutions to successful conclusions. Our forefathers in 1804 were a prime example. Here, in CSMS Magazine, we’re not interested in a sterile discussion about the militarist and maximalist attitude of the leaders of PUCH, who tried and failed with unimaginable consequences of what seemed to be a well justifying attempt to rid the country of fascism. Their military mishaps both in strategy and in tactic coupled with a bizarre and quirky mix of short-sidedness and a profound revolutionary conviction led to their miserable failure. “The dilemma of bringing Marxism-Leninism to the masses does not only rest with the social origin of the PUCH leaders [overwhelmingly mulattoes from high-middle to the highest echelon], but it also rests in many other reasons that constituted a serious hindrance to the advancement of the struggle,” notes Marc-Arthur Fils-Aimé in his essay on Tribute to the PUCH militants: forty years later. (Voir Honneur aux camarades du PUCH : Quarante ans après )

This pertinent assertion can’t be closer to the truth. The other reasons, not explicitly clarified by Fils-Aimé, lie in the haste to switch from non-violence to arm struggle without going through the strategic process of political awareness of the deprived masses, their need to see themselves as integral part of a movement designed solely to deracinate entrenched poverty in which they seemed condemned to live forever. However, to claim the biggest blunder committed by PUCH was the rush to take up arms or the use of extreme form of political activism to overthrow a fascist regime is overly stated. It could run the risk of sending millions of compatriots, who still believe that any means was justified to do away with Duvalier, into virtual political bewilderment. At a time when an unspoken consensus on the role of the Haitian left is utterly obvious, quoting Angels to prove that “ideological and political blunders [could] trigger a [new] kind of politic, lurching from the opportunism of the Right to the petit-bourgeois adventurism of the Left” is dangerously misconstrued. It risks taking us back to the old theoretical labyrinth, the frozen dogmatism that kept La Gauche stationary for years. If the haste to take up arms without educating and mobilizing the masses is the ultimate blunder, so educating, motivating and mobilizing the masses without empowering them with the means to protect themselves is equally dangerous. Both elements must be unequivocally linked to bring a revolution to bear. One can always direct the same criticism to En Avantin the Jean Rabel massacre. Hundreds if not thousands died after being mobilized and then left abandoned to face Jean Michel Richardson and Daniel Lucas—the heads of the Tonton Macoutes in the Jean Rabel area, who unleashed scores of their henchmen on the defenseless peasants.

United to forge a national consensus

The merger of PUDA and PEP was the ultimate expression of a complete break from the past— precisely with the way the old HCP was doing business—without rejecting the idea of creating a democratic, national and sovereign government. This idea was going to be embellished by Jacques Stephen Alexis in his 1959 Program for the New Independence. “Every Haitian, whatever his occupation and his desires, in this humiliating moment in our history, has a duty to work toward the creation of a mass movement that will allow the Haitian people to become masters of their own destiny,” Alexis noted in the PNI document. Here, the notion of class struggle takes a back seat to give way to a nationwide movement that would include bourgeois “nationalists” with the aim of giving birth to a national bourgeoisie—an important passage in the fight to create a solid working class. This was a two-pronged strategy designed to further the cause of strengthening the working class—critical phase toward democratic socialism—and to develop genuine spaces necessary for the establishment of revolutionary structures—indispensable elements in the road to bringing the country back from the brink.

This strategy was going to be the central theme of PUCH in 1969, despite the fact they had embraced arms struggle as their principal means of fighting the fascist regime. This theme was eloquently explained in PUCH political platform, which launched a revolutionary cry to anyone who opposed the small but powerful Haitian elite—a mixture of wealthy landowners, bourgeois comprador and their foreign multinational allies. If materialized, this would have been called “the revolutionary alliance, which would include the upper-middle class, the labor unions, the peasantry, and the exploited masses that make up the vast majority of the Haitian population.” Pp18. This alliance, in a first phase, “will allow the party to rescue the country from the grip of its enemies and will help restore the country’s sovereignty. This is the only way we could eliminate social contradictions plaguing the country—a dangerous element that constitutes a [serious] obstacle to social and economic progress….But a union of the working class and the peasantry is all the more urgent, for these two groups constitute the pivotal force of the democratic-national revolution and will [later] guarantee its evolution towards socialism.” Pp 19. This logic, however, did not hold, and the strategy was clumsily executed. In seeking the poetic justice, it was quickly discovered that there would be no poetry behind the justice, for the alliance of the so-called bourgeoisie nationale was pure mirage, more illusory than real. There is no doubt there are elements within the Haitian elite who nourished patriotic sentiments, as many leaders of the Haitian left were originated from the upper class. Roumain was a great example. But these elements represent a miniscule group, totally insignificant, certainly not capable of playing a vital role in helping to liberate the country.

Haiti must survive

By the fall of 1970, Papa Doc had succeeded in brutally suppressing the PUCH initiative. The movement failed because the leaders of PUCH overlooked a crucial element in national liberation struggles: mass mobilization and arm struggle are symbiotically linked. One cannot supersede the other. The PUCH ideologues, although rejected their class of origin to become revolutionaries just as Lenin says, did not seem to master the political savvy when it came to finding the right formula that would have given them the tools to sway the Haitian masses on their favor. In other words, their class of origin betrayed them. Was it political naïveté? No one knows for sure. But Gérald Brisson, fervent revolutionary and one of the brain masters behind the PUDA/PEP merger, believe that urban guerilla was pivotal in chasing the subliminal fear of the masses. “It will show that we’re not afraid of the beast, and that we’re ready to take on him head on with unforeseen fury.” Brisson himself was an economist who studied extensively the social contradictions that exist (to these days) between the different layers of the peasantry—relations between wealthy landowners and share croppers. But his acute understanding of the subject matter did not seem to help him. Moving ahead without bringing the masses along would almost mean political suicide.

By the fall of 1970, Papa Doc had succeeded in brutally suppressing the PUCH initiative. The movement failed because the leaders of PUCH overlooked a crucial element in national liberation struggles: mass mobilization and arm struggle are symbiotically linked. One cannot supersede the other. The PUCH ideologues, although rejected their class of origin to become revolutionaries just as Lenin says, did not seem to master the political savvy when it came to finding the right formula that would have given them the tools to sway the Haitian masses on their favor. In other words, their class of origin betrayed them. Was it political naïveté? No one knows for sure. But Gérald Brisson, fervent revolutionary and one of the brain masters behind the PUDA/PEP merger, believe that urban guerilla was pivotal in chasing the subliminal fear of the masses. “It will show that we’re not afraid of the beast, and that we’re ready to take on him head on with unforeseen fury.” Brisson himself was an economist who studied extensively the social contradictions that exist (to these days) between the different layers of the peasantry—relations between wealthy landowners and share croppers. But his acute understanding of the subject matter did not seem to help him. Moving ahead without bringing the masses along would almost mean political suicide.

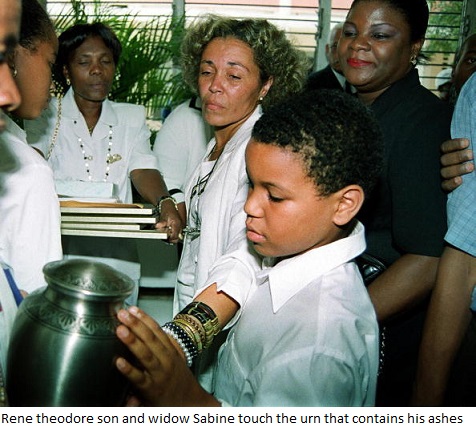

However, despite serious mishaps and perhaps lack of political correctness, no one can underestimate the revolutionary conviction behind the fury that catapulted these young patriotic Haitians to the collusion course with Papa Doc and his fascist regime. They fought and died courageously, and their death will go unnoticed if new generations of Haitians do not come forward to carry the torch left behind by these militants and others. In today’s fight to bring Haiti back from the brink, arm struggle may not be the proper means to achieve this awesome goal. But one thing remains constant: the corrupt state bureaucracy in Haiti cannot be eradicated without genuine popular organization. Let the past mistakes of the Left serve as important lessons for future struggles. As Haiti’s independence is now hanging by a thread, it is imperative that all Haitians have a patriotic duty to avoid our beloved country from sinking into history. Those who are now in power and claim to be the sun of the Left are nothing but sleazy politicians who at one time in their past flirted with progressive ideas, but they never moved away from their petit-bourgeois aspirations. They CANNOT represent the revolutionary leadership that Haiti needs to land on its feet. It is no time for tergiversations; it is time for political actions.

As we pay tribute to the PUCH martyrs and to all those who perished before them, we must remember that they will only live on through our political deeds. Manno Charlemagne says in one of his songs, “If we were to count all the bodies, Port-au-Price cemetery would probably join the one in Leogane.” (Leogane is a town located some ten miles south of Port-au-Prince.) The Haitian capital would probably not be enough to bury all of them. While we dream and long for freedom, we must realize that it will not materialize until the roses shiver and the still stubborn sun quivers its awful glow over the hills, valleys and mountains of the Haitian heartland. Only La Gauche can make this happen.

Note: Ardain Isma is the Chief Editor for CSMS Magazine. He is also a thinker and a novelist. His latest book, Midnight at Noon, was published by Educa Vision. Click on the link to order your copy:Midnight at Noon .