North Korea’s blowing up of its cooling tower was swiftly received with great enthusiasm in Washington, underscoring the eagerness by the strategists in the US capital to claim success for US diplomacy. Washington chief diplomacy Condoleeza Rice during the G-8 summit in Kyoto, Japan acknowledged that North Korea’s move to nuclear disarmament, which began by blowing up the tower and which will allow the United States access to 18,000 pages of operational records, is major procedural breakthrough in the quest to a nuclear free Korean Peninsula.

China was quick to capitalize on the North Korea’s gesture when the Chinese vice-Foreign Minister Wu Dawei challenged the US to follow through on its promise to remove the PDRK from the list of states that sponsor terrorism and to terminate application of the Trading with the Enemy Act. The Enemy Act is the one that bars US companies from doing business with countries considered to be the enemies of the State. The PDRK (People’s Democratic Republic of Korea) has already furthered its gesture by allowing the World Food Program to multiply its operational staff in the country and to speed up the permit process for food distribution in the country. The question remains: will the PDRK finally gives up it nuclear arsenal? In this article, Alex Lantier explains the logic behind this latest diplomatic maneuvering just north of the DMZ (demilitarized zone) in the Korean Peninsula.

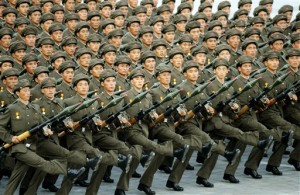

By blowing up the cooling tower of its Yongbyon nuclear facility yesterday and publishing a report on its nuclear program on June 26, North Korea signaled its willingness to begin a nuclear disarmament program. In accepting the report, while saying it will make as few concessions to North Korea as possible, Washington is acknowledging its political and military weakness in this crucial region, while leaving itself the option of later returning to a more belligerent policy.Pyongyang agreed to make such a report in October 2007, at six-party talks—including the US, China, Russia, Japan, South Korea, and North Korea—that began meeting in 2003 amid growing tensions between the US and North Korea. North Korea announced that it had a nuclear bomb in 2005, and has since been negotiating with the US to obtain security guarantees in exchange for concessions on its nuclear program.

North Korea did not file the declaration by the December 31, 2007 deadline, due to disagreements with the US over the contents. However, the Bush administration has accepted the present report and North Korean assurances of US access to its nuclear facilities.North Korea’s report stated that it had produced roughly 40 kg of plutonium—enough for 6 to 10 nuclear bombs, and within the range of 30 to 50 kg expected by US intelligence analysts. US officials said North Korea had agreed to allow US inspectors to collect independent samples of nuclear waste at Yongbyon, take samples of the reactor core, and access 18,000 pages of operational records.

North Korea did not file the declaration by the December 31, 2007 deadline, due to disagreements with the US over the contents. However, the Bush administration has accepted the present report and North Korean assurances of US access to its nuclear facilities.North Korea’s report stated that it had produced roughly 40 kg of plutonium—enough for 6 to 10 nuclear bombs, and within the range of 30 to 50 kg expected by US intelligence analysts. US officials said North Korea had agreed to allow US inspectors to collect independent samples of nuclear waste at Yongbyon, take samples of the reactor core, and access 18,000 pages of operational records.

US Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice told reporters at a G8 meeting in Kyoto, Japan that she believed the US had “the means by which to verify the completeness and accuracy of the document.”China’s vice-Foreign Minister Wu Dawei, host of the Beijing talks and the first recipient of the North Korean report, said that the US should “implement its obligations to remove the designation of [North Korea] as a state sponsor of terrorism and to terminate application of the Trading with the Enemy Act,”—a law banning US companies from trading with states judged hostile to Washington—with respect to North Korea.Washington did act to end North Korea’s listing under the Trading with the Enemy Act and has begun the 45-day process to remove North Korea from the terrorism list, but these moves will lead at most to a slight relaxing of North Korea’s crippling economic isolation and are in any case easily reversible.

In a June 26 press conference, Bush said: “The two actions America is taking will have little impact on North Korea’s financial and diplomatic isolation. North Korea will remain one of the most heavily sanctioned nations in the world.”US Defense Secretary Robert Gates added: “The reality is that there are so many other sanctions on North Korea because of its other behaviors that there’s really no practical effect of taking them off the terrorist list.”US officials have also questioned whether the North Korean report discloses all the plutonium it produced, noting that the report gives no information about any potential nuclear bombs or its alleged uranium enrichment program.

The administration is trying to appease bitter opposition to any easing of pressure on North Korea from the right wing of the Republican Party. John Bolton, the former Bush administration ambassador to the UN, said the accord was “shameful” and the “final collapse of Bush’s foreign policy.”Vice-President Dick Cheney’s response was even more remarkable, according to a June 27 account of a foreign policy meeting published in the New York Times. Upon receiving a question on Korea, Cheney “froze,” the newspaper reported.The Times continued: “For more than 30 minutes he had been taking and answering questions, without missing a beat. But now, for several long seconds, he stared, unsmilingly, at his questioner, Steven Clemons of the New America Foundation […] Finally he spoke: ‘I’m not going to be the one to announce this decision,’ the other participants recall Mr. Cheney saying, pointing at himself. ‘You need to address your interest in this to the State Department.’ He then declared he was done taking questions, and left the room.”

The Bush administration’s policy towards North Korea—isolating it and threatening it with military force, in order to break up a potential realignment in Northeast Asia unfavorable to US strategic and commercial interests—is in shambles. With the US military absorbed by bloody and unpopular occupations of Iraq and Afghanistan, US geopolitical influence is receding, even as the region’s strategic importance grows rapidly.Shortly after taking office in March 2001, the Bush administration broke off the talks with North Korea held by the Clinton administration. This effectively ended then-South Korean President Kim Dae Jung’s “Sunshine Policy” of building economic and political links to North Korea, which threatened to bring about greater regional integration between Japan, China, Korea, and the broader Eurasian continent. After the September 11, 2001 terrorist attacks, Bush named North Korea as part of the “axis of evil” and maintained diplomatic and military pressure on it throughout the initial stages of the Iraq occupation.

The Iraq war soon began to limit US influence in Northeast Asia, however. In May 2004 the US began to pull out some troops from South Korea, which has hosted US forces since the 1950-1953 Korean War, to send them to the Middle East. In February 2005 North Korea announced that it had nuclear weapons. It carried out a nuclear test blast with unclear results in October 2006, and Rice’s subsequent tour of the region to isolate North Korea failed to garner support. The February 2007 six-party accord to begin disarmament came on the heels of the Bush administration’s defeat in the November 2006 US mid-term elections.

The rudderlessness of Bush administration Northeast Asia policy is a matter of serious concern inside the US bourgeoisie. In testimony last month to the US Senate Foreign Relations Committee, Dr. Kurt Campbell of the Center for a New American Security said: “Some of the President’s closest advisers have told him to spend all his waking hours on selling an increasingly skeptical American populace on the necessity of continuing with the [Iraq] war. … Another set of advisers argue that the United States must begin to put Iraq in context and focus on other issues of importance, such as the drama playing out in Asia and in particular China’s dramatic ascent.”

Though Northeast Asia is still economically dependent on exports to the US, intraregional trade is growing rapidly. China has emerged particularly as an exporter of consum state sponsor of terrorism and to terminate application of the Trading with the Enemy Act er goods to wealthier markets in Japan and Korea, and Japan and Korea export capital goods to China. China overtook the US as South Korea’s largest trading partner in 2003, and in 2005 China-South Korea trade was $100 billion, versus $70 billion for Japan-South Korea and US-South Korea trade. In 2007 Japan-China trade was ¥ 29.36 trillion, versus ¥ 24.84 for Japan-US trade.China is also using its economic growth to fund a substantial increase in military spending, focusing largely on Taiwan and control of shipping lanes. The presence of North Korea as a buffer between China and well-equipped US and South Korean forces frees up resources that China would otherwise have to spend on an extensive military presence along the China-Korea border.

As US-China competition over key shipping lanes grows, the unpopularity of US military deployments in Japan and South Korea dating to the end of World War II is reaching crisis proportions, forcing a pull-back of US troops from certain controversial bases.

As the Sydney Morning Herald notes, “the Americans have been modifying their positioning of forces along the East-Asian coast […] The unpopular US forces are being wound down in South Korea and Japan’s Okinawa islands and relocated to Guam, a US territory. A lasting détente on the Korean peninsula will hasten the process.”

The ongoing mass demonstrations in South Korea against US beef imports, which have rocked the conservative government of President Lee Myung-bak, indicate the explosive tensions building up in the region. The demonstrations reflect not only opposition to lax sanitary procedures in the US meat industry, but broader political concerns—the presence of US military personnel in South Korea, and the US government’s backing for repressive, authoritarian regimes in South Korea in the 35 years after the Korean War.

Note: This article was first published on the SW website (www.wsws.org )

Also see Is Korean Nationalism fake or real?

Tensions rise on the Korean peninsula following nuclear test

It may be too late to reverse the North Korean missile development