In the wake of a resurging Russia and its power projection in Eurasia, the western powers have been forced to recognize a geopolitical reality: Russia cannot be contained. The question is: How do we get to China without Russia? Can Russia be circumvented? If there were any doubts in Russia’s resolves when it comes to prioritizing its strategic interests, the recent, geopolitical crises first in the Crimea, then in the Donbass and now in Syria should be sufficed to grasp the calculus that drives the Kremlin leadership in its commitment to ensuring Russia’s sustenance as a global power. Understanding the scope of its power projection and the wherewithal that it masters to craft its strategic deterrence, the hope to morph Russia as a junior partner of NATO—a hope or dream so cherished in the 1990s, especially after the dissolution of the USSR—has now been dashed. Russia does not seek to rebuild the old Soviet Union through the subjugation of former Warsaw Pact countries of Eastern Europe and Eurasia. In the article that follows, the authors take aim at “Moscow’s interests…. limited and focused on its near abroad….[the best way to understand] how Russia prioritizes its security challenges and how it assesses the security situation on its borders…a start to clearing up much of the uncertainty in Eurasia today.”

In the wake of a resurging Russia and its power projection in Eurasia, the western powers have been forced to recognize a geopolitical reality: Russia cannot be contained. The question is: How do we get to China without Russia? Can Russia be circumvented? If there were any doubts in Russia’s resolves when it comes to prioritizing its strategic interests, the recent, geopolitical crises first in the Crimea, then in the Donbass and now in Syria should be sufficed to grasp the calculus that drives the Kremlin leadership in its commitment to ensuring Russia’s sustenance as a global power. Understanding the scope of its power projection and the wherewithal that it masters to craft its strategic deterrence, the hope to morph Russia as a junior partner of NATO—a hope or dream so cherished in the 1990s, especially after the dissolution of the USSR—has now been dashed. Russia does not seek to rebuild the old Soviet Union through the subjugation of former Warsaw Pact countries of Eastern Europe and Eurasia. In the article that follows, the authors take aim at “Moscow’s interests…. limited and focused on its near abroad….[the best way to understand] how Russia prioritizes its security challenges and how it assesses the security situation on its borders…a start to clearing up much of the uncertainty in Eurasia today.”

__________________________________________________

How to avoid war with Russia

By Andrey Bezrukov, Mikhail Mamonov, Sergey Markdenov, Andrey Sushentov

Much has been said recently about the unpredictability of Russian foreign policy, and the resulting uncertainty. In reality, Moscow’s interests are quite limited and focused on its near abroad. Understanding how Russia prioritizes its security challenges and how it assesses the security situation on its borders is a start to clearing up much of the uncertainty in Eurasia today. This analysis focuses on critical situations that may develop this year into vital challenges to Russian interests, triggering a response from Moscow.

It has been two years since Russia found itself in the middle of a geopolitical tornado. Could it deliberately stay out of it? We believe not. In nature, wind emerges because of differential pressures between regions. Similarly, in politics, conflicts emerge from a change in the balance of power and destruction of the status quo. The collapse of regimes in Ukraine and in the Middle East created low-pressure zones, drawing neighboring countries into the regional storm. Having found itself in a hurricane, Moscow made its choice. It could have lowered its sails and followed the wind, but it preferred to keep to its course even if it meant sailing against the wind.

Moscow’s offensive had its achievements: Russia is holding the initiative and managing crises wisely for its own purposes. However, in recent months Russia missed at least two sensitive blows. The first was miscalculating the consequences of the public protests in Kyiv in late 2014; the second was underestimating the risk of a Turkish military provocation during Russia’s Syrian operation. However cautious Moscow is in its foreign policy, blind spots trouble every experienced operator.

In its worldview, Russia is a great-power chauvinist and a hard-power athlete. Modern Russia is a status quo player focused predominantly on its nearest abroad. Neither Russian security priorities nor its resources compel Moscow to project power beyond one thousand kilometers from its borders. The basics of Russia’s security strategy are simple: keep the neighboring belt stable, NATO weak, China close and the United States focused elsewhere. Russia supports and abides by international rules, but only until a third party ruins the status quo and harms Moscow’s security interests. When Russia sees the security environment around it as certain and predictable, it feels no need for intervention. But when uncertainty arises and a crisis occurs, Russia responds forcefully.

Logic of a U.S.-Russia Divide

How does Russia see its place in the geopolitics of today? It is clear that the rivalry between the two centers of geopolitical gravity—the United States and China—in defining the rules of international order is a defining process of the twenty-first century. And as the Atlantic bloc is gradually losing its weight, the United States has shifted from expanding to defending its positions. This American strategy may be tagged “new enclosure,” that is, creating exclusive zones enclosed against rivals (first and foremost China) with economic, political and other kinds of barriers.

How does Russia see its place in the geopolitics of today? It is clear that the rivalry between the two centers of geopolitical gravity—the United States and China—in defining the rules of international order is a defining process of the twenty-first century. And as the Atlantic bloc is gradually losing its weight, the United States has shifted from expanding to defending its positions. This American strategy may be tagged “new enclosure,” that is, creating exclusive zones enclosed against rivals (first and foremost China) with economic, political and other kinds of barriers.

As a result, Moscow assesses U.S. policy towards Russia as a preventive attack carried out before Russia restores its historic place after the period of crisis. Washington, Moscow assesses, sees the possibility of Russia, clamped deep in the continent, being prevented from being a serious economic rival and therefore unable to form an alternative center of power in Eurasia. A weakened Russia will be kept in fear of Chinese expansion, and will be forced to become an American partner in Washington’s major project for the twenty-first century: the containment of China. And as long as American elites aim for global leadership, there is no alternative to their strategy of weakening Russia. And there is no use looking for a conspiracy in this strategy—Russia simply happens to be in the way of America’s plans. It makes no difference to Washington whether Russian elites are pro- or anti-American; their position only affects the way the United States achieves its goals. With Putin as Russia’s president, Washington avoids the trouble of paying compliments to its opponent, and can easily trip Moscow up.

The way American elites refuse to abandon the idea of global leadership, Moscow cannot afford to be weak. Russia has always been under pressure from rival civilizations to the west and south—pressure that is still growing. The goal of the current sanctions war is to exhaust and drain Russia, making it use up its limited resources, creating feelings of despair and inevitability of collapse among the public. In this environment, Russia chooses to escape direct strikes and distract the offender, shifting the front line far from its territories.

Russia’s first attempt to seize the initiative was the “Turn to the East” and the 2015 BRICS Summit in Ufa, aimed at mobilizing its allies. But it was only successful in part. The BRICS countries were not ready to sacrifice their relations with the United States, and the “Turn” could not bring fast results to influence the current balance of power.

A second, more successful attempt was the Russian operation in Syria. Europe’s exhaustion from Ukraine and the migrant crisis contributed to its effectiveness. But the main reason was the stalemate in U.S. policy, between the declared goal of overthrowing Bashar al-Assad and the impossibility of allowing an ISIS victory. Trying to find a way out, the United States decided, at least temporarily, to accept Russia’s offer to change the game. But the general goal of making Moscow surrender never disappeared. And even though it is not a key short-term goal for the Washington, it will never resist the temptation to use emerging possibilities to weaken Moscow.

The Syrian Crisis and the Conflict With Turkey

From the Russian point of view, allowing ISIS to gain control over Syria and Iraq means a new influx of well-trained terrorists in the North Caucasus and Central Asia in five years. By some estimates, out of seventy thousand ISIS militants, up to five thousand are either Russians or citizens of CIS countries. Their return home will have an overwhelming influence on the already-fragile situation in the Russian Caucasus and Central Asian republics. In these circumstances, Moscow believes it is cheaper to fight Islamists in the Middle East than at home.

From the Russian point of view, allowing ISIS to gain control over Syria and Iraq means a new influx of well-trained terrorists in the North Caucasus and Central Asia in five years. By some estimates, out of seventy thousand ISIS militants, up to five thousand are either Russians or citizens of CIS countries. Their return home will have an overwhelming influence on the already-fragile situation in the Russian Caucasus and Central Asian republics. In these circumstances, Moscow believes it is cheaper to fight Islamists in the Middle East than at home.

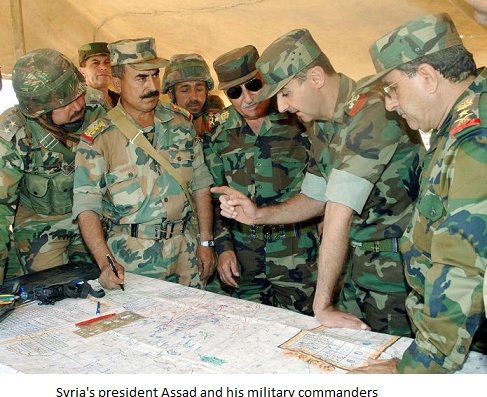

Russia’s strategy in Syria is advantageous, achieving a great deal with minimal resources and a relatively low level of involvement. In order to get what it wants, Russia only needs to disorganize—not entirely destroy—the terrorist infrastructure. Russia will be able to preserve the friendly regime in Damascus in one form or another, strengthen its first major naval base in the Mediterranean and retain its leadership in offshore gas projects in Syria, Cyprus and Israel.

Russia will consolidate its position in the Middle East as a country able to exercise expeditionary military campaigns. The Syrian operation displays the efficiency, accuracy and reliability of Russian arms capabilities, satellite communications and the GLONASS navigation system. All of this is clear evidence that Moscow preserves full sovereignty in twenty-first-century warfare.

Russia’s potential benefits from the Syrian campaign are great, but so are the risks. Russia unintentionally sparked confrontation with an important regional power, namely, Turkey. Ankara’s interest is to topple Bashar al-Assad, and it is using the fight against ISIS to combat Kurdish armed groups in Syria. It is not the first time that regional differences have arisen between Russia and Turkey, but it has been a century since they used force against each other.

In the worst-case scenario, Ankara and Moscow may now become the first parties to a revolution in warfare, where there is no front line or thousands of victims, but where the damage is devastating to space satellites, communication systems, logistical hubs and Internet infrastructure.

However, Russia’s greatest potential risk is getting drawn into the regional Sunni-Shia confrontation on the side of Iran, which is opposed by a coalition of Sunni states led by Saudi Arabia. Considering that the majority of Russian Muslims are Sunnis, Moscow should be especially cautious.

In this context, Russia will find it hard to ensure the support of the Syrian Sunnis who oppose ISIS. Drawing on its experience in Chechnya, Russia will aim to settle the Syrian conflict by enabling cooperation between the regime and leaders of Sunni communities who are ready to join the fight against terrorists. In the case of success, they will be the ones to fill the power vacuum after ISIS’s defeat—akin to what happened with the Kadyrov family in Chechnya.

The Cancer of Jihadi Terror

Regions where armed jihadi groups act are, of course, deeply interconnected. The flow of militants from Palestine, Libya, Syria and Afghanistan to the Caucasus and Central Asia and back is an urgent problem. Even if the coalitions fighting terrorists in Syria are successful, this will not mean a victory over terrorism in general. Most qualified militants and commanders would simply move from Syria to other countries (Iraq, Libya, Mali, Afghanistan, Somalia and so on). The insuperable crisis that threatens state institutions in Middle East and Africa also encourages the resilience of jihadi mercenaries. Moreover, in the last several years such mercenaries have come to organize global criminal economic networks and find support from some state authorities. Such groups cost little to sustain and may be enough to destabilize a whole region.

Like a cancer, international terrorism is dangerous because of the risk of metastasis, and its appearance in a certain place or in a certain time is just as difficult to predict. The worst scenario for Russia would be a collapse of a weak and poor Central Asian state, and its transformation into an uncontrollable territory ruled by armed groups with their own interpretation of Sharia law. This prospect is especially dangerous today, when Russia has fewer resources to support its allies than it did four years ago; its sharp reduction in investment for Kyrgyzstan is the first symptom.

The main buttress against this Central Asian scenario is the Russian economy. Revolutions and civil wars have their own demographic dynamics, and as long as young men from Tajikistan, Uzbekistan and Kyrgyzstan may come and earn their living in Russia, they will not join jihadi movements to overthrow political regimes at home. The first symptom of the emergent threat will be not domestic political events in poor post-Soviet republics, but statistical growth in sectors of Russian economy that traditionally rely on mass unskilled labor, like construction, retail and wholesale trade, housing and communal services.

With the slowdown of growth in Russia’s construction sector, the most difficult situation in 2016 will be in Tajikistan, where the current leadership is exacerbating tensions by cracking down on the Islamist opposition. This measure is considered a violation of the status quo, a set of peace rules that ended the 1992–97 civil war in that country. At that time, allowing Islamists into political life was among the most important conditions of ending the confrontation. The Tajik authorities have been escalating their opposition to the Islamic Renaissance Party, creating the threat of a tactical union with more radical groups. The possibility of a new civil war in Tajikistan would inevitably force Russia to intervene.

The Situation in Nagorno-Karabakh

The Nagorno-Karabakh conflict remains one of the most dangerous challenges in the Caucasus. Each side in the conflict has entered 2016 without any sign of compromise over the key issues—namely, the status of Nagorno-Karabakh and some other Azerbaijani territories controlled by Armenian forces, as well as the problem of refugees.

The possibility of exacerbation in the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict scares both Russia and the West. A “defrosting” that would lead to the deployment of international peacekeeping troops also bothers Iran, which claims that the conflict should be settled without the participation of any nonlocal powers. However, the Russian-Turkish confrontation, given the strategic cooperation between Azerbaijan and Turkey as well as between Armenia and Russia, raises the risk of a conflict that spreads well beyond the Caucasus region.

For Russia, a breakdown of the fragile status quo will have appalling consequences. First, it will bring into question the prospects of the Eurasian integration projects (the CSTO and EEU), for there is no consensus among their members concerning political and military support for Armenia. Second, it may sharpen the conflict of interests between Moscow and Baku, and even repeat the Georgian scenario of 2008. Third, the weakening of Russia’s position will inevitably lead some to suggest a wider internationalization of the peace process, which will ensure that Russian influence decreases.

Two main conditions are required for the negative scenario to develop in Nagorno-Karabakh: the deterioration of the Russian-Turkish confrontation, and an unprovoked escalation as a result of snowballing incidents on the border. The conflict with Moscow may push Ankara to increase its military support for Azerbaijan in order to press harder, not only on the unrecognized Nagorno-Karabakh, but on Armenia itself. Still, the military and political balance between Yerevan and Baku will not let either side achieve an overwhelming advantage, and will contain the conflict.

Ukraine in 2016

The dynamics of a potential Ukrainian crisis in 2016 will be defined by the political situation in Kyiv. In implementing the Minsk Agreements, the ball has long been in Ukraine’s court. In the first half of the year, Ukraine will be adopting amendments to its constitution that will establish a special status for the Donbass within the state and set rules for local elections in some areas of the Donetsk and Luhansk regions. Theoretically, the Ukrainian leadership may agree to settle the conflict, although throughout last year it was trying its best to avoid doing so. In practical terms, it remains highly unlikely.

The latest municipal elections demonstrated that President Petro Poroshenko has already moved past the point when he had free hand for enacting reforms. Now his approval rating is slowly sinking, the ruling coalition is getting weaker and the position of Poroshenko’s key parliamentary ally, Prime Minister Yatsenyuk, is openly disputed. Even if he wanted to, the president would not be able to gain the necessary support in the Rada for a compromise over the Donbass. Ukrainian politics will undoubtedly radicalize with the central government’s progressive political weakening.

Two symptoms of the Donbass crisis will drag on until the second half of 2016. The first one will be the failure to adopt amendments to the constitution proposed by the president. These amendments do not comply with the Minsk Agreements; nonetheless, the Ukrainian authorities have been referring to them as proof of their commitment to Minsk. If the Rada does not approve them in the current session, it will not be able to discuss amendments to the constitution for another year.

The second one is a vote on the bill concerning elections in the Donbass, which is supposed to be approved by the sides of the conflict (Kyiv and the rebels). Judging by the situation today, the two sides’ positions are incompatible, and it is difficult to imagine it will be approved—not to mention the Rada vote, where the same factors arise that have hindered the introduction of the president’s constitutional reform.

Most likely, in February or March it will become obvious that a settlement, or at least meaningful steps towards it, will not happen in the first half of 2016. This implies that the key question will be whether Ukraine is ready to resume hostilities.

A new full-scale war in the Donbass is hardly expected. The outcome of previous armed clashes between Kyiv and the People’s Republics does not leave much hope for the former. Besides, it is of particular interest for Russia not to let Donetsk and Luhansk lose. The western European partners among the “Normandy Four” are also against war, which Paris and Berlin see as a threat to security of the continent. Still, there is a possibility that Kyiv will decide to launch a new offensive in the Donbass because of renewed internal political struggles in Ukraine.

In case the war resumes, the Donetsk and Luhansk People’s Republics (DNR and LNR) have a clear political goal: to gain control over the whole territory of Donetsk and Luhansk regions. For Kyiv, the key military risk is losing new towns in the Donbass, should a new campaign fail. Moscow’s decision to limit the counteroffensive of the Donbass militia will depend on two conditions. The first is how valuable in the critical moment it will find the positions of its Ukrainian partners, whom it tends to listen to. The second is whether Moscow will achieve mutual understanding with Berlin and Paris on recognizing Kyiv’s responsibility for unleashing the hostilities.

We should stress that neither the Donbass nor Moscow wants a new war. It would cause great risks and huge, inevitable losses. Owing to its Syrian operation, Russia has started to find a new modus operandi in its relations with the West, and it knows the value of this achievement. The Kyiv authorities are still too popular with Western Europe for it to recognize their responsibility for the civil war. Ukraine realizes that its diplomatic positions are deteriorating, and will hardly dare to start a new war in such uncertain circumstances.

At the same time, Kyiv will struggle to find allies that would support such a war against the Donbass—except for the United States. The involvement of Turkey, much discussed in Ukraine, is rather doubtful. Naturally, Ankara will do everything to scare Moscow by supporting radical Crimean Tatar organizations or Kyivan hawks. However, it is hard to believe that Turkish military involvement in Ukraine will find understanding in Washington; this is something that the alliance can live without.

A fast settlement to the Ukraine crisis is highly unlikely, but so is war. It seems that the situation of 2015 will repeat itself in 2016: Kyiv will continue pressuring Donbass by means of bombardment and siege, avoiding meaningful negotiations on a settlement. The most patient actors will prevail.

Potential Conflicts in Asia

Security threats in East Asia will be defined by the U.S.-China rivalry. Tensions are growing in relations between Beijing and the most important military allies of Washington in the region, Japan and Australia. East Asia’s most vulnerable security points in 2016 will be the Taiwan issue and the growing frictions in the South and East China Seas.

The victory of the Democratic Progressive Party in Taiwan’s presidential elections has left much unsettled. If the DPP publicly rejects the principle of one country or declares Taipei’s independence, Beijing will have nothing to do but to use military power to suppress what it sees as separatists. The risk of this scenario for the first time in four years has encouraged Washington to resume military deliveries to Taiwan: in 2016 the plan is to deliver arms adding up to $1.8 billion. Beijing considers this step a direct signal of support to the Taiwanese authorities, and has promised a harsh reaction. It is highly expected that China will not only introduce sanctions against major arms suppliers to Taiwan, but will also pressure U.S. companies that operate in the Chinese market.

The other permanent source of friction in East Asia is Washington’s active involvement in territorial conflicts in the South and East China Seas. In October 2015, the destroyer USS Lassen started its patrol within twelve nautical miles of artificial islands built by China in the South China Sea, and in December, American bombers flew close to the Spratly Islands. Beijing’s response to such actions may be very harsh. Demonstrating the seriousness of Beijing’s intentions, on December 17, 2015, a Chinese submarine conducted a simulated attack on the aircraft carrier USS Ronald Reagan. If the two sides continue this kind of dangerous military behavior, the risk of a collision is high. They had a similar experience in 2001, when a Chinese jet crashed into a U.S. EP-3 reconnaissance plane. Apart from that, in 2016 there is a growing possibility of mutual hostilities between China and the United States in cyberspace.

Another frustration for Beijing comes from Australia and Japan’s actions in the South and East China Seas. Tokyo intends to station artillery batteries and ships along two hundred islands on a 1,400-kilometer expanse, which will impede movement of Chinese military ship towards the western Pacific. In August 2015, Japan approved the largest military budget in post–World War II history ($27 billion). And during the APEC Summit, Prime Minister Shinzo Abe stated that his country is ready to consider participating in patrols of disputed territories in the South China Sea. At the same time, Australian flights over the disputed islands are not so much disturbing to China as they are irritating. And yet the possibility of an armed collision with Japanese or Australian military ship is high. Beijing is convinced that Washington is not ready to be pulled into all-out conflict with China, even for their key allies’ sake, while Japan’s image as a historical enemy of China may stimulate escalation.

Key Risks for Russia in 2016

Our perspective on the future of anti-Russia sanctions in 2016 is negative. Sanctions will not be lifted because this will require fulfillment of several conditions: the Minsk-2 Agreement has to be fully implemented, military provocations in the Donbass have to stop, opponents of sanctions in the EU have to win over proponents of sanctions and the EU itself has to be ready to reject solidarity with the United States in the issue of sanctions—or else, President Obama has to support the EU and lift sanctions half a year before the end of his presidency. All this cannot be achieved in 2016. Therefore, sanctions will remain, and Russia must get used to the unfavorable state of its external affairs.

Despite western Europe’s fatigue with Ukraine and the freezing of the Donbass conflict, U.S. support for the Kyiv regime in 2016 will not subside, and in the worst case scenario, we will see U.S. arms deliveries to Ukraine.

On the Syrian front, there are short-term risks of Russia getting giddy with its success, which may cause uncontrollable escalation of Russian-Turkish relations and the possibility of direct collision with Ankara. As a result, Russia has already found itself in a trap, set by those who want to see Russia stuck in the Middle East and relations with its neighbors to further deteriorate. Despite Moscow’s desire to demonstrate its power on every occasion, Russia may not afford to fall into such traps in the future: Syria is not Russia’s key front line.

In 2016, the waves of destruction from the Middle East will increase the risk of escalation of conflicts in the Caucasus, Nagorno-Karabakh and in Central Asia, especially with growing instability in Tajikistan. Popular unrest within Russia’s CIS allies may raise the question of Moscow’s involvement.

The world’s largest economies will continue failing to make headway, keeping oil prices at a record low. But the expanding zone of military action in the Middle East, the exacerbation of Saudi-Iranian tensions or destabilization within Saudi Arabia may change these calculations entirely.

China, India, Brazil and South Africa will be consumed with their own domestic problems. And despite their sympathies with Russia’s positions in Asia and Latin America, their banks and businesses will not do anything that could cause problems in their relations with the United States.

Choosing Between Two Evils

It is obvious that in 2016 Russia will have to choose between bad and very bad alternatives. Positive change may be expected no sooner than seven or eight years from now, when a new generation of elites will come to power in the United States and Europe, and may again consider Russia a strategic ally and a business partner.

What can Moscow do to make this possibility come true and to increase its own chances?

First, it should be prudent, preserve its power and avoid getting dragged into full-scale wars and lengthy confrontations. It has succeeded in doing so up until now.

Second, it has to keep patiently building its relations with western Europe, which is gradually growing to realize the importance of maintaining political dialogue and economic ties with Russia. Upcoming elections in key European countries and the United States leave hope that transatlantic solidarity will cease to be an axiom and Europe will finally regain its own voice.

Third, Russia cannot afford friction and misunderstandings with its closest neighbors and allies—namely, China, Belarus, Kazakhstan and Armenia. It is not a question of interstate relations, but the necessity to deepen mutual understanding between elites, be they business, military or youth.

Lastly, Russia’s priorities for 2016 include the strategic goal of stabilizing greater Eurasia as a guarantee of Russia’s survival and prosperity. Cooperation with China, India, Iran, SCO partners and ASEAN countries will help create a system of collective security, build a pan-Asian transport and energy infrastructure and ensure the formation of the rapidly growing $4 billion Eurasian market, which is of critical importance to Russia.

Andrey Bezrukov is a strategy advisor at Rosneft and Associate Professor at MGIMO University (Moscow).

Mikhail Mamonov is a senior analyst with Foreign Policy Analysis Group and advisor with the Russia-China Investment Fund.

Sergey Markedonov is a senior analyst with Foreign Policy Analysis Group and Associate Professor at the Russian State University for the Humanities.

Andrey Sushentsov is an Associate Professor at MGIMO University (Moscow), program director at the Valdai Club and director at the Foreign Policy Analysis Group.

Image: Wikimedia Commons/kremlin.ru.

Like us on Facebook: www.facebook.com/csmsmagazine